We recently had the opportunity to chat with one of our contributors Øyvind Sandbakk on Episode 5 of the Training Science Podcast. One part of the discussion focussed on the unique challenges this Winter Olympic Games poses on the athletes and support teams. As we did for the Tokyo Summer Games, we leverage this conversation to share the 5 key factors athletes and support teams considered and are currently applying in Beijing. Those recommendations are inspired by Øyvind’s recent publication in the Journal of Science in Sport and Exercise. Fortunately, most recommendations will be applicable to athletes and their teams preparing for future international competition.

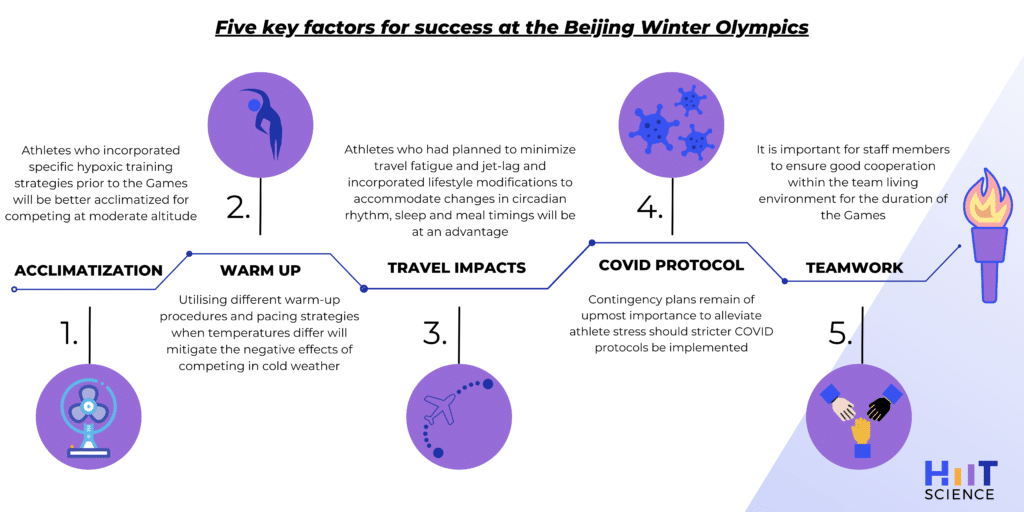

1) Hypoxic training: Yes! But don’t forget altitude acclimatization

These Beijing Games will be held mostly at 1700 m elevation. While this might be an advantage for sports involving short burst of effort due to lower air drag, sports with longer efforts taxing predominantly the aerobic system will be negatively affected.

The lowered oxygen pressure contributes to decreased arterial blood oxygen saturation (i.e., 5.5% reduction per 1000-m elevation during maximal exercise), leading to less oxygen delivery to working muscles and a consequent impairment of endurance performance (1).

This may be further exacerbated for well-trained endurance athletes with a high VO2max compared to athletes with lower endurance capacity (2). Other factors such as differences in the hypoxic ventilatory response and oxygen kinetics during exercise might also play a role (2). Therefore, it is important to incorporate specific training strategies in order to improve performance at moderate altitude, such as:

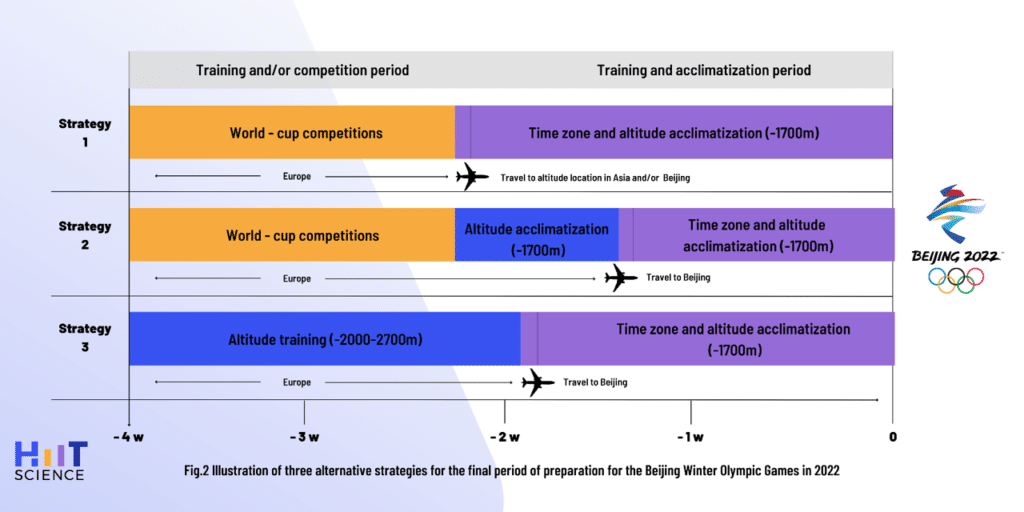

- In the year(s) prior to the Olympics, train for more than 60 days and participate in several competitions) at or above~1700 m.

- Perform 10–14 days of acclimatization at an altitude similar to that at which the Olympic competitions will take place (~1700 m), either at the Olympic venue itself or at other locations in Asia or in Europe (which may require later adjustment to the time zone in Beijing).

- An alternative strategy involves living and training for 14–21 days in a camp above 2000 m, followed by 7–10 days tapering at ~1700 m.

- To maximize erythropoiesis, maintain adequate levels of iron (>30 ng/mL ferritin) prior to altitude, in combination with individualized oral supplementation with iron (~100–200 mg daily) during altitude exposure as required.

2) Be warmed up to face the cold

Competitive endurance skiers are typically exposed to ambient temperatures ranging from – 20°C to as high as +10°C. With ambient temperature likely below 0°C, body temperature rises, while the temperature of the skin falls due to cooling of the superficial musculature (3), which may subsequently influence an individual’s capacity to produce power due to reduced exercise economy (1). In addition, previous reports indicate that wind may amplify the effects of cold temperature.

These potential negative effects are associated with increased strain on the muscles and more rapid fatigue due to reduced oxidative enzyme activity, nerve and muscle excitability and nerve conduction (4).

While the altitude could be seen as the main restrictive factor, managing the cold environment can be another challenge that needs to be faced by athletes and staff members.

To mitigate, athletes and their support teams are encouraged to:

- Optimize individualized warm-up procedures and pacing strategies at different temperatures

- Prepare clothing that is appropriate for different and potentially changing environmental conditions

- Prepare clothing that ensures optimal maintenance of core temperature

- Develop a procedure for maintaining body temperature during the period between warm-up and the competition itself

- Adapt warm-up procedures and pacing strategies to ambient environmental conditions, with particular focus on the initial part of the race

- Athletes with asthmatic symptoms should plan for appropriate treatment in connection with high ventilation at cold temperatures

3) Prepare to face the jet lag

Alongside the challenges of competing at moderate altitude and potential cold weather, several additional stressors need to be taken account. Going to Beijing is a long journey. For athletes competing in these events, travel to Beijing involves crossing eight time-zones during 12–15 h fights, resulting in both travel fatigue and jet lag (5). Therefore, athletes should:

- Arrange to arrive at least one day earlier for each hour of difference between their time zone and that in Beijing.

- During each of the 3 or 4 days prior to departure, shift sleep and eating schedule by 0.5–1 h towards what it will be in Beijing.

- To facilitate good sleep, take afternoon flights travelling east.

- To avoid dehydration during travel, drink adequate volumes of non-alcoholic, non-caffeinated fluids.

- Plan timing of exposure to (day)light to optimize adaptation of your circadian rhythm and consider supplementation with 2–5 mg melatonin at appropriate times if needed.

- Schedule meals and social contacts in accordance with the local time in Beijing.

- Short (20–30 min) naps can aid recovery and help maintain normal alertness.

- Avoid intensive training during the first few days after arrival.

4) Covid issues still remain

Competitions will be performed with reduced support-teams and without spectators. This will challenge athletes to take more responsibility for their training and equipment, as well as recovery and mental preparations (e.g., attaining their full potential in the absence of spectators), while coaches and support-teams must prepare to work more efficiently and organized than previously. They will be keeping the following issues in mind:

- Cancelled or restricted world cup competitions in the preparations for the Olympics have limited the possibilities both for qualifying for the Olympics and for optimal preparation for competition. Accordingly, each nation has had alternative strategies for handling these challenges as well as possible.

- Routine testing for COVID-19 and possible quarantine in connection with competitions limit training and preparation for many athletes.

- Whether appropriate or not, current rules in China around Covid limit athletes’ access to training facilities where they might typically expect access to be.

5) Teamwork makes the dream work!

While it may sound logical, most of the athletes will have to live together for a fair bit of time in the lead up to the Games. Therefore, it is important for staff members to ensure high cooperation within the team leading into and during the Olympic games. Indeed, this point is paramount due to the extensive COVID restrictions in place in Beijing. Successful teams will be the ones that are supporting each other.

Conclusions

As with each Olympics, all have their own unique challenges. Beijing 2022 is no exception, with additional restrictions related to the COVID-19 situation. Successful coaches and athletes can prepare as best they can, but additionally, need to support one another and expect the unexpected.

References

- Sandbakk, Ø., Solli, G.S., Talsnes, R.K. et al. Preparing for the Nordic Skiing Events at the Beijing Olympics in 2022: Evidence-Based Recommendations and Unanswered Questions. J. Of Sci. In Sport And Exercise 3, 257–269 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-021-00113-5

- Chapman RF, Stager JM, Tanner DA, Stray-Gundersen J, Levine BD. Impairment of 3000-m run time at altitude is influenced by arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(9):1649–56. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318211bf45.

- Layden JD, Patterson MJ, Nimmo MA. Effects of reduced ambient temperature on fat utilization during submaximal exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(5):774–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200205000-00008.

- Oksa J. Neuromuscular performance limitations in cold. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2002;61(2):154–62. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v61i2.17448.

- van Janse Rensburg DCC, Jansen van Rensburg A, Fowler P, Fullagar H, Stevens D, Halson S, Bender A, Vincent G, Claassen-Smithers A, Dunican I, Roach GD, Sargent C, Lastella M, Cronje T. How to manage travel fatigue and jet lag in athletes? A systematic review of interventions. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(16):960–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101635.