Understanding the impacts of heat on the body is key to performance in hot and humid climates

Scott Bayvel is a South African born professional triathlete currently living in Queensland, Australia.

We asked Scott about his experiences of preparing to compete in the heat. Here are his responses:1) Is any form of exercise ok to acclimate to the heat? Or should it be more event/ sport-specific?

I think that to fully acclimate to heat you must perform the primary activities that will be in action in the given target event. So the better you can simulate event conditions within the preparation phase during acclimation, the better your chances of being acclimated for it come race or event.2) How long do you need to acclimate before a race in the heat?

Based on my experience, 4-6 weeks is a good amount of preparation time for acclimating for a hot race. But this is all dependent on the current environment/season you are in during this lead-up period. For example, coming out of winter might require more time for heat preparation, while if you are in a hotter climate you might need less.3) How do you modify the HIIT training approach to heat?

With HIIT, the focus is always on the session first and then the heat acclimation protocol can follow afterwards. Take a sauna session for example. In this case, the HIIT session should take priority, with the heat prep tagged on as an added stressing factor post-workout.

Figure 1. Scott racing in a triathlon

Dr Julia Casadio (PhD) is a senior performance physiologist at High-Performance New Zealand.

Julia also leads the team’s Tokyo heat strategy and so is well placed to answer questions concerning heat acclimatization from the researcher/ practitioner perspective. Here are her responses:1) What are the benefits of heat acclimatization for someone not competing in the heat?

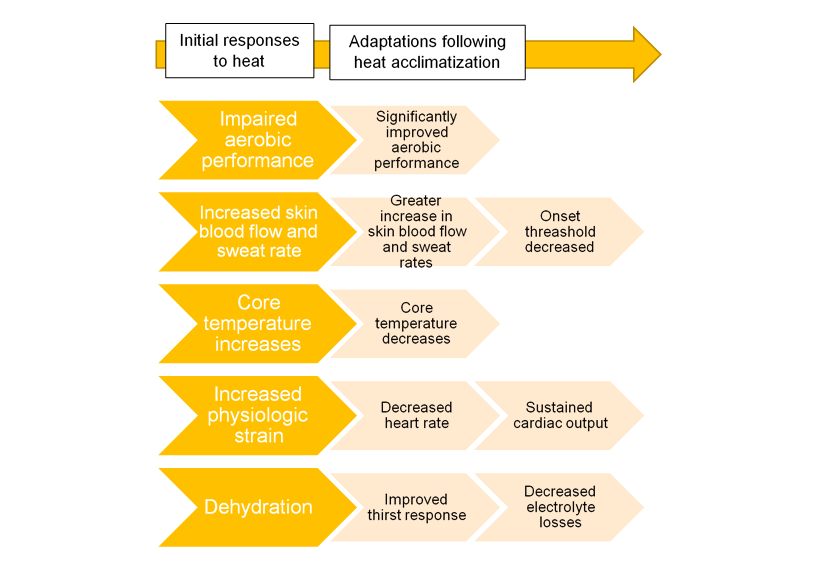

While heat acclimatization provides a host of thermoregulatory adaptations to support performance in the heat, many of the physiological benefits can appeal to those with no need to compete in the heat. Some of these benefits include increases in plasma volume, haemoglobin mass, maximal aerobic capacity (VO2max), and lactate threshold, as well as reductions in heart rate at sub-max intensities and carbohydrate metabolism. Some of the key adaptations are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Initial responses to heat and adaptations that occur following heat acclimatization

2) Are there endurance gains?

For sure! The list of benefits we can see from Figure 1 should strongly appeal if you are an endurance or team sport athlete. The big question is, does this translate to improved endurance performance in temperate or cool conditions? Robust randomised control trials have shown that the answer is, unfortunately, no:‘there is no further endurance performance gain from training in the heat, compared with training in ‘normal’ conditions, when competing in a cool environment (Mikkelsen et al., 2019).’However, research from ‘real world’ settings suggests that when heat acclimatization is applied at the ‘right’ time, such as during a preseason training camp (Racinais et al., 2014) or during a training phase where aerobic fitness could be reduced (Casadio et al., 2016), endurance gains in cool conditions are indeed evident.

3) What are the limitations of heat acclimatization?

Without a doubt, heat acclimatization will enhance performance in hot conditions, but there is still no conclusive evidence that this will consistently translate to cool conditions as well. Heat is a powerful stimulus, so careful consideration of how and when heat is applied to a training plan is key.‘It is possible to overdue heat acclimatization to the point where performance is actually impaired (Reeve et al., 2019).’Athletes who are fighting illness or infection are at risk of experiencing exertional heat illness, and therefore should delay any heat sessions until they are 100% healthy. For tips on how to add heat to training with athletes in a practical setting see Gibson et al., 2019 and Casadio et al., 2017.

‘Remember that responses to heat stress and heat acclimatization can vary immensely between individual athletes.’

4) If you don’t have access to a heat chamber, is it enough to go into a sauna or hot tub after training? If so, how many times do you need to go and what is the benefit?

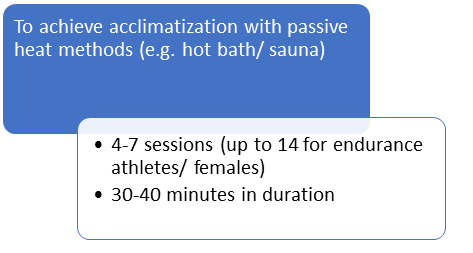

Yes, sauna or spa bathing, immediately following a training session, is a great alternative if you don’t have access to a heat chamber as the benefits are generally the same as heat acclimatization. For example, see Zurawlew et al.‘The time taken to achieve heat acclimation varies between males and females.’In males, most thermoregulatory and physiological adaptations can be expected with 4-7 passive heat sessions of 30-40 min duration, with further thermoregulatory benefits evident with 10-14 sessions (recommended for long-distance endurance events in the heat). For females, we know that a longer period of heat stimulus (10-14 d) is needed for initial benefits like a reduction in core temperature and sub-maximal heart rate. See Figure 3 for a summary of passive heat methods for acclimatization.

Figure 3. Achieving heat acclimatization with passive heat methods – key considerations

5) What is the most important variable to manipulate – temperature or humidity?

You can’t have heat acclimatization without some amount of heat (≥27oC). The hotter the ambient temperature, sauna, spa, or heat chamber, the greater the heat stress, which will drive the rise in body temperature.‘It’s important to note that the key elements of a useful heat acclimation session are to get hot (core temp ≥38.5oC) and be dripping with sweat.’This can be achieved with both hot and dry (E.g. 40oC, 20% RH) or warm and humid (E.g. 30oC, 80% RH) conditions. In fact, both examples provide a similar level of heat stress when you consider apparent (feels like) temperature. However, at a given hot temperature, as you begin to increase humidity, there is an exponential increase in heat stress, which is why this year’s Tokyo Games are expected to be the hottest ‘feels like’ Olympics in history.

‘At the end of the day both temperature and humidity need to be considered.’

Figure 4. Julia Casadio during preparation for the Rio 2016 Olympics

Dr Andi Drake is a consultant endurance coach for British Athletics, manager of Leeds Talent Hub, and the personal coach to several world-class racewalkers.

Andi completed his PhD in applied physiology and has experience in preparing athletes for competition in hot environments, including the IAAF World Athletics Championships in Doha, Qatar and the Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. Here are his responses to the heat acclimatization question we posed to him:1) What changes are we looking for in athletes following a period of heat acclimatization?

The recent 2019 IAAF World Athletics Championships in Doha and this year’s Tokyo Olympic Games were/will be in hot and humid conditions. When exercising in the heat, elevated core body temperature often sees a reduction of exercise capacity/performance. Heat acclimatization, pre-/per-exercise cooling and fluid ingestion are methods employed to combat the impact of heat strain on the athlete.‘Heat acclimatization impacts on a range of thermoregulatory, cardiovascular, fluid-electrolyte, metabolic and molecular responses.’For the long-distance athletes (race walk & marathon) competing in these two hot and humid Championships, we are looking for a lower heart rate, lower core temperature and higher sweat rate during exercise to demonstrate heat acclimatization, together with improvements in perceptions of thermal strain and comfort. The athletes we are talking about are highly trained – where differences are often in perceptual measures, and this informs our strategies in term of how we use cooling methods during the event, as well as race tactics.

2) How long do the effects of heat acclimatization last?

‘Highly trained athletes likely retain heat acclimatization adaptations longer than untrained.’All the adaptations decay without a regular heat stimulus, influenced by the length of heat acclimatization and level of conditioning. To counter, we keep athletes “topped up” in between bouts of heat acclimatization to negate this decay, e.g. using hot (40°) 45-minute baths post-training or using an environmental chamber 1-2 days per week. This understanding of the time course of heat acclimatization and decay helps us plan final preparation for championships in hot and humid environments. The important of heat acclimatization strategies is highlighted by Tom Bosworth in his Tweet posted after the World Athletics Championships which were held in Doha, 2019. See Figure 5.

Figure 5. Tweet from Tom Bosworth, one of Andi’s athletes, highlighting the importance of heat acclimatization strategies in his Tweet posted after Doha, 2019

3) How do you acclimatise an athlete? What procedure should we follow?

For the 2019 World Athletics Championships, we put the athletes through 60 minutes of easy intensity race walking on a treadmill at 32° and 80% humidity for five consecutive days (See Figure 6). We saw desirable changes in core temperature, exercising heart rate, sweat rate, and ratings of perceived exertion, thermal comfort and thermal sensation. We did this 8 weeks prior to competition and 4 weeks prior to leaving for a heat and altitude camp, keeping the athletes topped up as above. This strategy was designed to remove the need to acclimatize upon arrival at the preparation camp, which may have interfered with the final four weeks of Championships preparation. Moreover, based on physiological and perceptual measures, we were able to create bespoke pre- and per-cooling strategies for each athlete to impact core temperature and/or to mask thermal sensations as appropriate, e.g. including fuel & fluid replacement, ice-cold scarves/hats/hand ice blocks/water.‘Thanks to a rigorous strategy through 2019, we have our preparation plan for 2020 in place, ready for the Olympic Games!’

Figure 6. Tom Bosworth in the Leeds Beckett Environmental Chamber with British Athletics Physiologist, Dr Andy Shaw. Temperature and humidity are shown in the bottom left corner.

Top Ten Tips for Heat Acclimatization from the HIIT Science Team

Based on the responses from Scott, Julia and Andi, we pulled together ten top tips that could help you and your athletes prepare for competition in hot environments:- Heat acclimatization can enhance performance in hot and humid conditions

- Responses to the heat are individual.

-

- It is important to consider the individual and be specific when preparing for competition in hot environments, considering the sporting modality, the race/ competition conditions, and the individual’s level of fitness and experience in the heat.

-

- Heat acclimatization is not just about temperature.

-

- It is also important to consider humidity. During periods of heat acclimatization, the key is to ensure that the athlete is hot (core temp ≥38.5oC) and dripping with sweat.

-

- The time needed to achieve heat acclimatization varies.

-

- Hot baths or sauna after training can achieve heat acclimatization, to some degree, after just 6 days. Other protocols can take up to 6 weeks. But this is dependent on the sessions performed and the conditions they are performed in.

-

- Key physiological changes to look for when aiming for heat acclimatization include: A lower heart rate, lower core temperature and higher sweat rate during exercise.

- Use the latest research to develop a heat acclimatization plan suitable for your context.

-

- For tips on how to add heat to training with athletes in practical settings, see Gibson et al., 2019 and Casadio et al., 2017.

-

- Maintenance of heat adaptations varies between athletes.

-

- Highly trained athletes likely retain adaptations longer than untrained. But for all athletes, the adaptations decay without a recurring heat stimulus

-

- Alternative heat adaptation methods, which can also be used to prevent adaptation decay, include sauna or spa bathing.

-

- These methods should be practised immediately following a training session for the maximum benefit.

-

- Pre-cooling can provide a further boost for endurance performance.

-

- Each athlete has a different objective and subjective responses to heat, so it’s important to create bespoke pre-cooling strategies for each athlete.

-

- Do not overlook how hot it ‘feels’ in the competition context.

-

- The combination of temperature and humidity can make places feel hotter than they actually are. The Tokyo Olympics are set to be the hottest ‘feel’ games ever for this reason. It is important that coaches prepare athletes for such a feeling.

-