We all know the amazing benefits of high-intensity interval training (HIIT), such as improved cardiovascular system function, muscle metabolism, systemic health and of course exercise performance. But one aspect that has received relatively less discussion is: What should we (or should we not) be eating to support adaptations to HIIT training, so we can get the most ‘bang for your buck’ from our hard work?

I recently published a paper addressing this topic in the journal Nutrients, titled: “Supplements and Nutritional Interventions to Augment High-intensity Interval Training Physiological and Performance Adaptations”, alongside a distinguished group of experts in the area of sport nutrition from across Canada and the United States. The review focused predominantly on the first 2 of 3 major physiological HIIT targets discussed throughout HIIT Science, namely, the aerobic oxidative (cardiovascular and peripheral oxidative systems) and the anaerobic glycolytic response, and the nutritional supplements we can ingest to actually improve adaptations to these responses, and subsequently endurance performance.

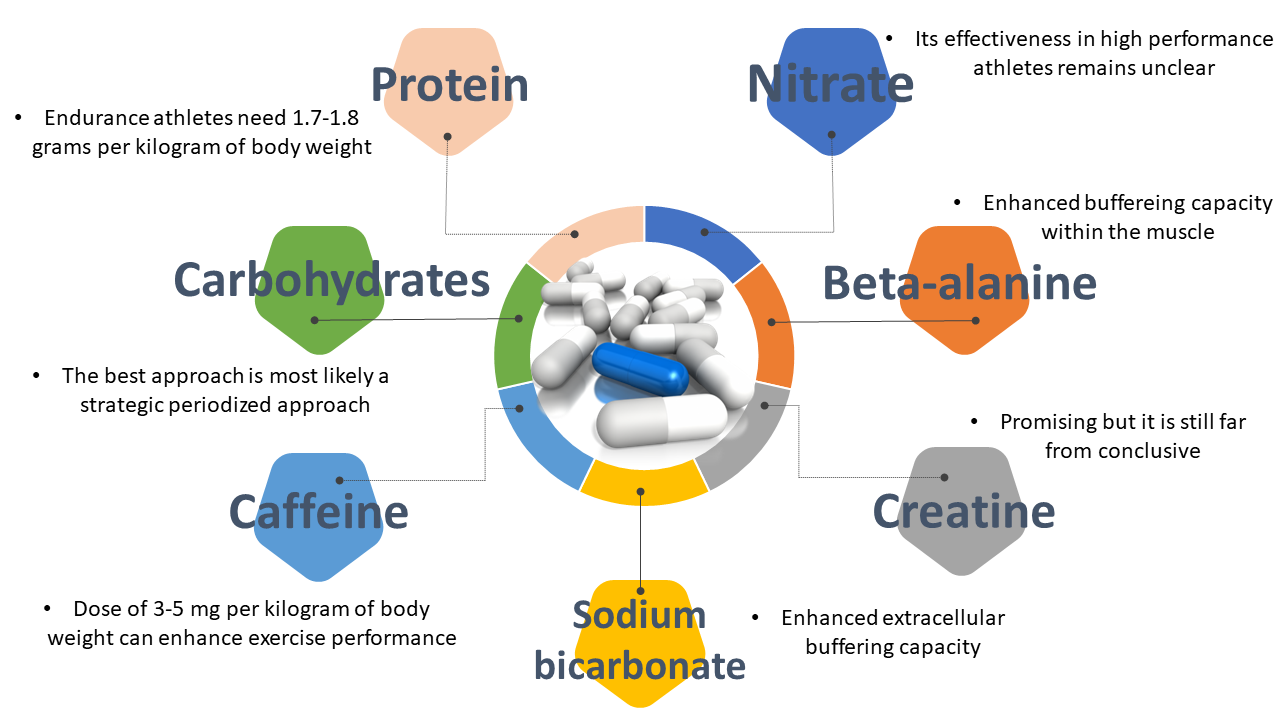

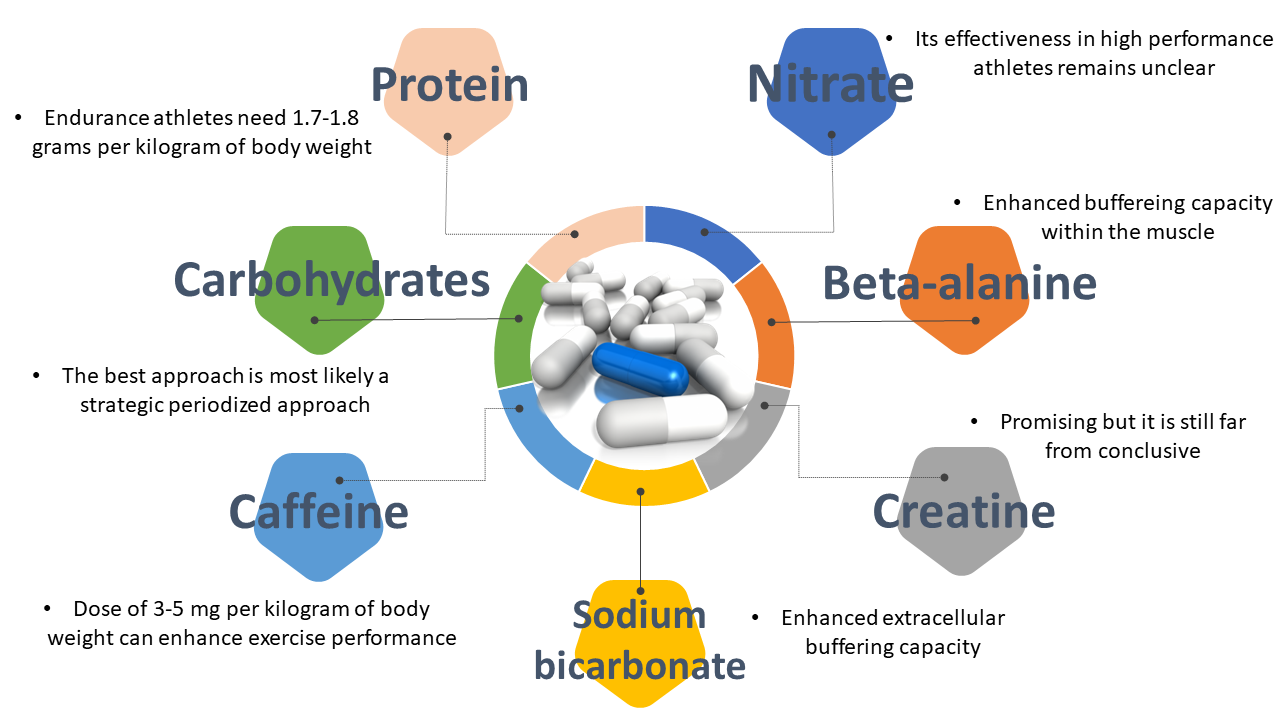

Five supplements made the shortlist, including creatine monohydrate, caffeine, nitrate, sodium bicarbonate, and beta-alanine. We also discussed the impact of protein, as well as manipulating carbohydrate availability.

Creatine

Creatine is made from three amino acids and is a well-known supplement used to enhance muscle mass and strength gains in bodybuilders. In theory, creatine supplementation can provide the muscle with more phosphocreatine. Importantly, phosphocreatine can be broken down very rapidly to resynthesize ATP, as required to support muscular contractions.

Caffeine

Caffeine is one of the most widely studied supplements in the area of sport nutrition. Caffeine, in a dose of 3-5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight can enhance exercise performance in a variety of ways, such as by acting as an adenosine receptor antagonist that leads to a reduction in perception of pain (basically, it makes exercise feel easier). It also acts directly on the muscle and improves the speed the muscle can contract and relax. Despite these well-studied mechanisms, there appears to be some (although limited) performance benefits.

Caffeine

Caffeine is one of the most widely studied supplements in the area of sport nutrition. Caffeine, in a dose of 3-5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight can enhance exercise performance in a variety of ways, such as by acting as an adenosine receptor antagonist that leads to a reduction in perception of pain (basically, it makes exercise feel easier). It also acts directly on the muscle and improves the speed the muscle can contract and relax. Despite these well-studied mechanisms, there appears to be some (although limited) performance benefits.

Sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate, more well known as baking soda, is another strong candidate supplement that may enhance HIIT performance. We all know that burning sensation we get when doing repeated sprints. To be clear, this sensation is more likely due to an increase in hydrogen ions (the acid part), and not the lactate (the substrate). We have several ways to buffer those nasty hydrogen ions, and one is by increasing the bicarbonate levels in the blood.

Sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate, more well known as baking soda, is another strong candidate supplement that may enhance HIIT performance. We all know that burning sensation we get when doing repeated sprints. To be clear, this sensation is more likely due to an increase in hydrogen ions (the acid part), and not the lactate (the substrate). We have several ways to buffer those nasty hydrogen ions, and one is by increasing the bicarbonate levels in the blood.

Protein

Protein is important, not only to build muscle, but also to build the metabolic machinery, such as muscle enzymes and mitochondria.

Protein

Protein is important, not only to build muscle, but also to build the metabolic machinery, such as muscle enzymes and mitochondria.

Conclusion

Overall, research into sodium bicarbonate and beta-alanine supplementation show promise for enhancing acute HIIT adaptations and performance, while nitrates generally appear to lack effectiveness for high level athletes. Caffeine supplementation shows promise, especially during periods of carbohydrate-restricted training. While creatine supplementation has great theoretical potential to assist with HIIT performance and adaptation, based on the current available literature seems far from conclusively effective. Endurance athletes should aim for 1.7-1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to enhance recovery and adaptations within the muscle. Last, but not least – manipulating carbohydrate intake strategically during training appears to enhance both the molecular muscle adaptations to HIIT, and potentially performance.

About the author:

Conclusion

Overall, research into sodium bicarbonate and beta-alanine supplementation show promise for enhancing acute HIIT adaptations and performance, while nitrates generally appear to lack effectiveness for high level athletes. Caffeine supplementation shows promise, especially during periods of carbohydrate-restricted training. While creatine supplementation has great theoretical potential to assist with HIIT performance and adaptation, based on the current available literature seems far from conclusively effective. Endurance athletes should aim for 1.7-1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to enhance recovery and adaptations within the muscle. Last, but not least – manipulating carbohydrate intake strategically during training appears to enhance both the molecular muscle adaptations to HIIT, and potentially performance.

About the author:

Dr. Scott Forbes is an Associate Professor in the department of Physical Education at Brandon University and is an Adjunct Professor in the faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies at the University of Regina. Dr. Forbes has completed the International Olympic Committee diploma in Sports Nutrition and is a Clinical Exercise Physiologist (CSEP) and holds a Performance Specialization (CSEP). His primary research examines various nutritional and exercise interventions to enhance performance in a variety of populations. Dr. Forbes has published over 50 peer-reviewed publications, 3 book chapters, and has been an invited speaker at several international conferences. Dr. Forbes has worked as a personal trainer as well as an athlete consultant for several professional and varsity level sport teams.

References

Dr. Scott Forbes is an Associate Professor in the department of Physical Education at Brandon University and is an Adjunct Professor in the faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies at the University of Regina. Dr. Forbes has completed the International Olympic Committee diploma in Sports Nutrition and is a Clinical Exercise Physiologist (CSEP) and holds a Performance Specialization (CSEP). His primary research examines various nutritional and exercise interventions to enhance performance in a variety of populations. Dr. Forbes has published over 50 peer-reviewed publications, 3 book chapters, and has been an invited speaker at several international conferences. Dr. Forbes has worked as a personal trainer as well as an athlete consultant for several professional and varsity level sport teams.

References

One less known aspect of creatine is that it helps the muscle take on more glycogen, by increasing the expression of GLUT-4, a glucose transporter in the muscle.Glycogen is another fuel source that can be rapidly used to support high-intensity exercise. Tomcik and colleagues (1) examined a group of well-trained cyclists (VO2max~65 mL/kg/min) who completed a series of 120-km time trials with alternating 1- and 4 km-sprints every 10 km. Participants were randomized to supplement with or without creatine alongside a moderate or a high amount of carbohydrate. Creatine facilitated a greater uptake of glycogen into the muscle (determined with muscle biopsies) and improved the final 4-km sprint. It seems promising, but can it actually improve HIIT? To examine, forty-three active men were randomized to four weeks of HIIT with and without creatine (2). The creatine group improved ventilatory threshold to a greater extent than HIIT training alone. Improvements in aerobic power and performance however were not enhanced with creatine. Overall, this supplement could have promise, but its usefulness remains far from conclusive.

Caffeine

Caffeine is one of the most widely studied supplements in the area of sport nutrition. Caffeine, in a dose of 3-5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight can enhance exercise performance in a variety of ways, such as by acting as an adenosine receptor antagonist that leads to a reduction in perception of pain (basically, it makes exercise feel easier). It also acts directly on the muscle and improves the speed the muscle can contract and relax. Despite these well-studied mechanisms, there appears to be some (although limited) performance benefits.

Caffeine

Caffeine is one of the most widely studied supplements in the area of sport nutrition. Caffeine, in a dose of 3-5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight can enhance exercise performance in a variety of ways, such as by acting as an adenosine receptor antagonist that leads to a reduction in perception of pain (basically, it makes exercise feel easier). It also acts directly on the muscle and improves the speed the muscle can contract and relax. Despite these well-studied mechanisms, there appears to be some (although limited) performance benefits.

One intriguing area of caffeine supplementation is during carbohydrate restricted training.Kasper and colleagues (3) investigated the impact of caffeine with carbohydrate mouth rinsing on high-intensity interval running following an evening bout of exercise to deplete carbohydrate stores. Caffeine and carbohydrate mouth rinsing improved their HIIT session performance. Another emerging topic in this area is the nutrition-gene interactions. For example, the presence of a caffeine gene, known as CYP1A2, allowed scientists to predict who would respond (or not) to caffeine supplementation (4).* Overall, it is recommended that fatigued athletes, or athletes in a carbohydrate restricted state who want to hammer a hard HIIT session may want to consider caffeine to enhance their HIIT performance.

Sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate, more well known as baking soda, is another strong candidate supplement that may enhance HIIT performance. We all know that burning sensation we get when doing repeated sprints. To be clear, this sensation is more likely due to an increase in hydrogen ions (the acid part), and not the lactate (the substrate). We have several ways to buffer those nasty hydrogen ions, and one is by increasing the bicarbonate levels in the blood.

Sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate, more well known as baking soda, is another strong candidate supplement that may enhance HIIT performance. We all know that burning sensation we get when doing repeated sprints. To be clear, this sensation is more likely due to an increase in hydrogen ions (the acid part), and not the lactate (the substrate). We have several ways to buffer those nasty hydrogen ions, and one is by increasing the bicarbonate levels in the blood.

Sodium bicarbonate has been consistently shown to improve acute exercise over all-out durations lasting 1 to 10 minutes by 2 to 3%.Over a training cycle, there is also evidence that more chronic sodium bicarbonate use may be effective (5). Importantly, to get a performance benefit, you need to consume a high dose (~0.3 grams per kilograms of body weight) to increase your endogenous bicarbonate levels. The issue unfortunately is that high doses of sodium bicarbonate lead to gastrointestinal distress. Scientist are working on various strategies to use this supplement without the side effects. A modified loading protocol, which involves taking smaller doses over 2 days (instead of taking one large dose) led to higher blood bicarbonate concentrations without the gastrointestinal side effects (6). Thus, there is hope! Next steps for researchers are to see how this modified protocol might influence HIIT performance and subsequent adaptation over time. Beta-alanine Beta-alanine is another supplement known to enhance buffering capacity. Beta-alanine is a precursor for carnosine, a molecule found inside the muscle that can accept a hydrogen ion.

Research has shown that supplementing with beta-alanine (3-6 grams per day for 28-days) increases intramuscular carnosine levels (7).Beta-alanine has been shown to improve 10-km time trial performance following 3 to 6 weeks of endurance training (8, 9) and cycling time to exhaustion at 110-120% peak power output following five weeks of sprint interval training (10). We speculate that the enhanced buffering capacity within the muscle may allow athletes to push a little harder in each training session that over time could lead to improved adaptations. For anyone considering beta-alanine, it is important to mention that you may experience an innocuous tingling sensation. Nitrate Eat your beets, spinach, and green leafy vegetables and gain an advantage! Sounds like my mom talking to me. Those food sources contain nitrates. Nitrates are important to increase nitric oxide levels, and nitric oxide is an important regulator of blood flow. Nitric oxide has also been shown to make your mitochondria (the power plant of the cell) work more efficiently. Importantly, nitrate supplementation seems to have a greater impact on fast-twitch fibers (11) and therefore may be ideal for HIIT. The usefulness of nitrate supplementation for high performance athletes performing HIIT however remains unclear, and short term studies in elite athletes have been shown to lack effectiveness (12).

Protein

Protein is important, not only to build muscle, but also to build the metabolic machinery, such as muscle enzymes and mitochondria.

Protein

Protein is important, not only to build muscle, but also to build the metabolic machinery, such as muscle enzymes and mitochondria.

Sophisticated studies measuring protein requirement have found that endurance athletes need much more protein than previously thought (13).For example, endurance athletes may need 1.7-1.8 grams per kilogram of body weight (more than double the RDA for non-exercising individuals) and similar amounts in fact to levels used by bodybuilders. However ingesting more than 1.7 g/kg of body weight of protein has not shown evidence of further support to training adaptations or performance (14). Carbohydrates Carbohydrates and their effect on training adaptations appear more complex than most believe. There is strong evidence that training with low carbohydrate availability (training in a fasted state or by eating a low carbohydrate diet) forces the muscles to become better at burning fat. Presently however, the data suggests that the best approach to carbohydrate intake with athletes is to use a periodized approach (15). Periodized carbohydrate intake refers to a strategic training plan where athletes train under periods of low and high carbohydrate availability. For all supplements and dietary strategies, context and individual differences (such as genetics, training status, and gender) may impact subsequent adaptations and are critical to consider.

Conclusion

Overall, research into sodium bicarbonate and beta-alanine supplementation show promise for enhancing acute HIIT adaptations and performance, while nitrates generally appear to lack effectiveness for high level athletes. Caffeine supplementation shows promise, especially during periods of carbohydrate-restricted training. While creatine supplementation has great theoretical potential to assist with HIIT performance and adaptation, based on the current available literature seems far from conclusively effective. Endurance athletes should aim for 1.7-1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to enhance recovery and adaptations within the muscle. Last, but not least – manipulating carbohydrate intake strategically during training appears to enhance both the molecular muscle adaptations to HIIT, and potentially performance.

About the author:

Conclusion

Overall, research into sodium bicarbonate and beta-alanine supplementation show promise for enhancing acute HIIT adaptations and performance, while nitrates generally appear to lack effectiveness for high level athletes. Caffeine supplementation shows promise, especially during periods of carbohydrate-restricted training. While creatine supplementation has great theoretical potential to assist with HIIT performance and adaptation, based on the current available literature seems far from conclusively effective. Endurance athletes should aim for 1.7-1.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to enhance recovery and adaptations within the muscle. Last, but not least – manipulating carbohydrate intake strategically during training appears to enhance both the molecular muscle adaptations to HIIT, and potentially performance.

About the author:

Dr. Scott Forbes is an Associate Professor in the department of Physical Education at Brandon University and is an Adjunct Professor in the faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies at the University of Regina. Dr. Forbes has completed the International Olympic Committee diploma in Sports Nutrition and is a Clinical Exercise Physiologist (CSEP) and holds a Performance Specialization (CSEP). His primary research examines various nutritional and exercise interventions to enhance performance in a variety of populations. Dr. Forbes has published over 50 peer-reviewed publications, 3 book chapters, and has been an invited speaker at several international conferences. Dr. Forbes has worked as a personal trainer as well as an athlete consultant for several professional and varsity level sport teams.

References

Dr. Scott Forbes is an Associate Professor in the department of Physical Education at Brandon University and is an Adjunct Professor in the faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies at the University of Regina. Dr. Forbes has completed the International Olympic Committee diploma in Sports Nutrition and is a Clinical Exercise Physiologist (CSEP) and holds a Performance Specialization (CSEP). His primary research examines various nutritional and exercise interventions to enhance performance in a variety of populations. Dr. Forbes has published over 50 peer-reviewed publications, 3 book chapters, and has been an invited speaker at several international conferences. Dr. Forbes has worked as a personal trainer as well as an athlete consultant for several professional and varsity level sport teams.

References

- Tomcik, KA, Camera, DM, Bone, JL, Ross, ML, Jeacocke, NA, Tachtsis, B, Senden, J, VAN Loon, LJC, Hawley, JA, Burke, LM. Effects of Creatine and Carbohydrate Loading on Cycling Time Trial Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50: 141-150, 2018.

- Graef, JL, Smith, AE, Kendall, KL, Fukuda, DH, Moon, JR, Beck, TW, Cramer, JT, Stout, JR. The effects of four weeks of creatine supplementation and high-intensity interval training on cardiorespiratory fitness: a randomized controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 6: 18-18, 2009.

- Kasper, AM, Cocking, S, Cockayne, M, Barnard, M, Tench, J, Parker, L, McAndrew, J, Langan-Evans, C, Close, GL, Morton, JP. Carbohydrate mouth rinse and caffeine improves high-intensity interval running capacity when carbohydrate restricted. Eur J Sport Sci 16: 560-568, 2016.

- Guest, N, Corey, P, Vescovi, J, El-Sohemy, A. Caffeine, CYP1A2 Genotype, and Endurance Performance in Athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50: 1570-1578, 2018.

- Edge, J, Bishop, D, Goodman, C. Effects of chronic NaHCO3 ingestion during interval training on changes to muscle buffer capacity, metabolism, and short-term endurance performance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 918-925, 2006.

- Marcus, A, Rossi, A, Cornwell, A, Hawkins, SA, Khodiguian, N. The effects of a novel bicarbonate loading protocol on serum bicarbonate concentration: a randomized controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 16: 41-4, 2019.

- Stellingwerff, T, Anwander, H, Egger, A, Buehler, T, Kreis, R, Decombaz, J, Boesch, C. Effect of two beta-alanine dosing protocols on muscle carnosine synthesis and washout. Amino Acids 42: 2461-2472, 2012.

- Santana, JO, de Freitas, MC, Dos Santos, DM, Rossi, FE, Lira, FS, Rosa-Neto, JC, Caperuto, EC. Beta-Alanine Supplementation Improved 10-km Running Time Trial in Physically Active Adults Front Physiol 9: 1105, 2018.

- Smith, AE, Moon, JR, Kendall, KL, Graef, JL, Lockwood, CM, Walter, AA, Beck, TW, Cramer, JT, Stout, JR. The effects of beta-alanine supplementation and high-intensity interval training on neuromuscular fatigue and muscle function. Eur J Appl Physiol 105: 357-363, 2009.

- Bellinger, PM, Minahan, CL. Additive Benefits of beta-Alanine Supplementation and Sprint-Interval Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48, 2417-2425, 2016.

- Jones, AM, Ferguson, SK, Bailey, SJ, Vanhatalo, A, Poole, DC. Fiber Type-Specific Effects of Dietary Nitrate. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 44: 53-60, 2016.

- McQuillan, JA, Dulson, DK, Laursen, PB, Kilding, AE. Dietary Nitrate Fails to Improve 1 and 4 km Cycling Performance in Highly Trained Cyclists. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 27: 255-263, 2017.

- Kato, H, Suzuki, K, Bannai, M, Moore, DR. Protein Requirements Are Elevated in Endurance Athletes after Exercise as Determined by the Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation Method. PLoS One 11: e0157406, 2016.

- Forbes, SC, Bell, GJ. Whey Protein Isolate Supplementation While Endurance Training Does Not Alter Cycling Performance or Immune Responses at Rest or After Exercise. Front Nutr 6: 19, 2019.

- Hawley, JA, Lundby, C, Cotter, JD, Burke, LM. Maximizing Cellular Adaptation to Endurance Exercise in Skeletal Muscle. Cell Metab 27: 962-976, 2018.