I was privileged to speak at two conferences this past weekend, to two distinct audiences about HIIT Science. The first was the

CSEP conference in Niagara Falls for the

Gord Sleivert memorial address; the audience consisting largely of university professors and postgraduate students. The second was to a group of practitioners in Toronto at the

RCCSS conference. For the larger CSEP conference, notwithstanding the great honour of giving Gord’s address, I was additionally privileged to have the session chaired by a leader in the science of HIIT,

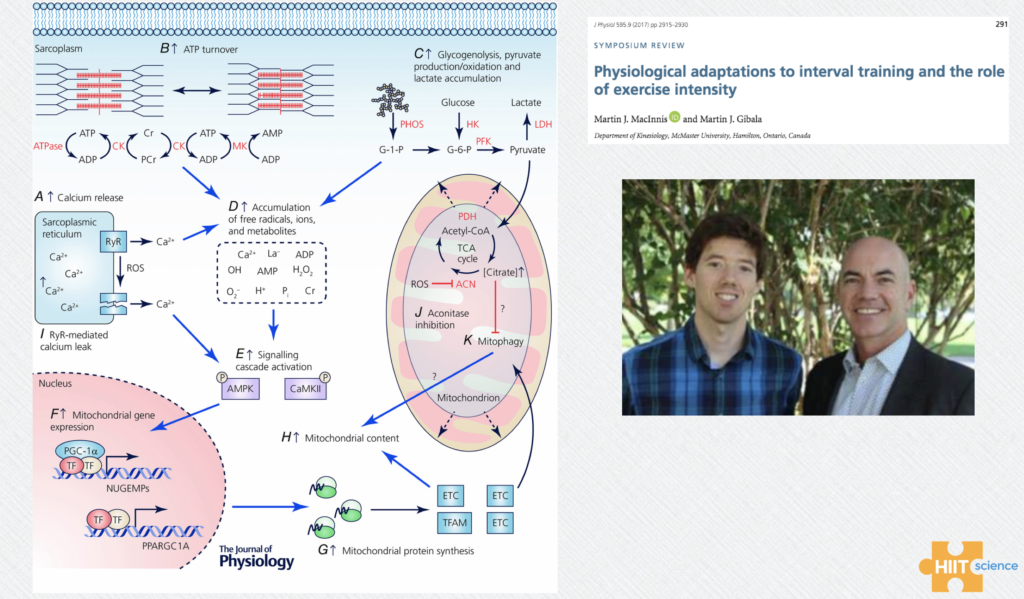

Dr Martin Gibala. Dr Gibala and MacInnis’

mechanistic figure on the metabolic adjustments that occur with HIIT in our muscle cells features in our book and course and provides a reference as to why we adapt with HIIT (Figure 1).

Prior to my talk, Dr Gibala and I discussed the two main aims of HIIT Science – raising awareness of the science of HIIT, but additionally appreciating the importance of

context in its application. This, we believe, is our great divide. Such challenges have been spoken on at length by

Martin,

Steve Ingham and many others. As a case in point, note how Canada’s two national conferences for sport science / exercise physiology (

CSEP) and sport performance application (

SPIN) occurred at the same time in two separate cities.

Acknowledging this before the talk, Dr Gibala asked me the obvious question: how might we begin to bridge the divide? How could we do a better job of teaching context, building pathways for our

semi-pros who desire a career in helping others perform better?

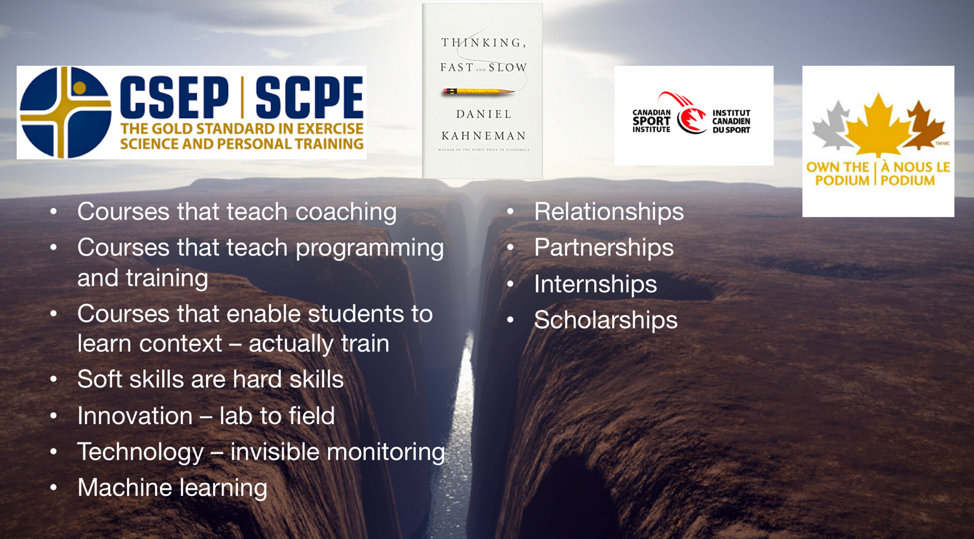

I thought about the question before my talk and added one slide to the end of my presentation, shown here (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The great divide.

Interestingly, the slide provoked more discussion from the CSEP group than anything else from the lecture. The

Daniel Kahneman reference thinking fast and thinking slow relates to

Aaron Coutts‘

editorial on the importance of being able to work fast and slow within a high performance environment. Both processes can be used to optimize a system’s performance – we all have a role to play, and my points related to what each side could contribute through partnerships. Remember that reference to CSEP and the Canadian government sport performance entities are simply representative organizations. The great divide is a global issue and includes amateur-professional sporting teams in the mix.

Why is this important?

We all have to start somewhere, and those of us drawn to the science of sport performance will, in our experience, often begin as

semi-pros. As described by our friend

Cesar Meylan, this may actually be an important first step of the pathway for the applied sport scientist, as sport experience (doing) means the practitioner can relate well to the head coach, understand jargon, and apply creativity to the application of the science. In essence, the semi-pro already began a portion of their professional development when they were growing up. They learnt some of that all-important context.

But fast-forward to today, where the twenty- or thirty-something semi-pro needs to evolve. Our background, love of sport, and

innate human altruism make us want to not just know more, but use our knowledge and experience to help others. So if one wants to learn how to help others achieve sporting success, what immediately comes to mind? Obviously – go to university to learn how to become a sport performance expert of some kind. These learning institutions promise knowledge and insight into this type of work – knowledge that prepares you.

But move another 4-10 years, and 1-3 degrees later – why is it that we often feel ill-equipped to help an athlete, or any person for that matter, make progress towards their goals? We lack a true understanding of

context and there’s been little if any connection of the dots between the science and its application.

Why the divide?

Clearly there’s a divide, but why? To start, most academics in university don’t know context. The teachers are not to blame, but they simply don’t know. Why would they? They’ve never had the experience. Martin and I began there too, and didn’t understand context ourselves until we got our chance to enter the high performance world. This experience bestowed hard lessons, but today allows us the ability to step back and forth across the void as needed, perhaps enabling us the ability to provide something a bit more digestible for everyone; academics and practitioners alike.

But to finish this point, we are today left with two issues on both sides of the divide that keep the worlds separate; we believe that both need addressing:

- Academic centres currently cannot teach context.

- A workforce in the high performance setting, who understand context, could use a sharpening of their knowledge.

Where to from here?

The thousands of professional and amateur sport programs and teams around the world, from all different codes, are in competition with one another. That’s the nature of sport. Margin of error and difference between winning and losing is tiny. Each practitioner within these organizations play important roles that contribute to the success or failure of their machine. With sharpened knowledge, the practitioner charged with forming training content has the advantage over their competition, as they can work “on the fly”, making the right decisions in the contextual moment, when it matters. For our practitioner colleagues, we hope that the Science and Application of High Intensity Interval Training, book and course, will be a resource that allows a sharpening of your knowledge, to allow you to improve your performance, in your context.

But what about our

100,000 graduating university students in the sport sciences, many of whom desire a pathway working in sport?

I asked a number of professors at the CSEP conference: Where do the students go after their degree?

Answer: A fraction get another degree, but the majority – no idea….

So, while many of those students may lack the aptitude, surely the system can do better collectively for those who desire the sport performance pathway; especially considering the technological advantages we have at our disposal today. Conference delegates approaching me after the talk expressed a genuine desire for action. One suggestion was to use HIIT Science as a vehicle to show both context, as well as how one moves between the science and practice – potentially alongside practicum or laboratory-based courses. While we acknowledge our video medium will only take us so far, it may provide a start, a look inside the walls of some of today’s high-performance settings, where we can begin to get a glimpse of what preparation looks like at the coal face of elite sport.

Stay tuned for a look behind the scenes of HIIT Science and a chance to meet the 20+ lecturers that came together to make this happen.

Note: If you’re an academic, lecturer, professor, or sport governing body administrator, and you can envisage something like this working within your program, please sign up through the separate form below so we can get in touch with you.

[convertkit form=781956]

And if you are a university student or already embedded practitioner, and you feel the HIIT Science content is something your organization needs to be offering, be sure to lead up and make your administration aware of us.

Thanks for reading everyone. HIIT Science is just about ready to serve you…

We all have to start somewhere, and those of us drawn to the science of sport performance will, in our experience, often begin as semi-pros. As described by our friend Cesar Meylan, this may actually be an important first step of the pathway for the applied sport scientist, as sport experience (doing) means the practitioner can relate well to the head coach, understand jargon, and apply creativity to the application of the science. In essence, the semi-pro already began a portion of their professional development when they were growing up. They learnt some of that all-important context.

But fast-forward to today, where the twenty- or thirty-something semi-pro needs to evolve. Our background, love of sport, and innate human altruism make us want to not just know more, but use our knowledge and experience to help others. So if one wants to learn how to help others achieve sporting success, what immediately comes to mind? Obviously – go to university to learn how to become a sport performance expert of some kind. These learning institutions promise knowledge and insight into this type of work – knowledge that prepares you.

But move another 4-10 years, and 1-3 degrees later – why is it that we often feel ill-equipped to help an athlete, or any person for that matter, make progress towards their goals? We lack a true understanding of context and there’s been little if any connection of the dots between the science and its application.

Why the divide?

Clearly there’s a divide, but why? To start, most academics in university don’t know context. The teachers are not to blame, but they simply don’t know. Why would they? They’ve never had the experience. Martin and I began there too, and didn’t understand context ourselves until we got our chance to enter the high performance world. This experience bestowed hard lessons, but today allows us the ability to step back and forth across the void as needed, perhaps enabling us the ability to provide something a bit more digestible for everyone; academics and practitioners alike.

But to finish this point, we are today left with two issues on both sides of the divide that keep the worlds separate; we believe that both need addressing:

We all have to start somewhere, and those of us drawn to the science of sport performance will, in our experience, often begin as semi-pros. As described by our friend Cesar Meylan, this may actually be an important first step of the pathway for the applied sport scientist, as sport experience (doing) means the practitioner can relate well to the head coach, understand jargon, and apply creativity to the application of the science. In essence, the semi-pro already began a portion of their professional development when they were growing up. They learnt some of that all-important context.

But fast-forward to today, where the twenty- or thirty-something semi-pro needs to evolve. Our background, love of sport, and innate human altruism make us want to not just know more, but use our knowledge and experience to help others. So if one wants to learn how to help others achieve sporting success, what immediately comes to mind? Obviously – go to university to learn how to become a sport performance expert of some kind. These learning institutions promise knowledge and insight into this type of work – knowledge that prepares you.

But move another 4-10 years, and 1-3 degrees later – why is it that we often feel ill-equipped to help an athlete, or any person for that matter, make progress towards their goals? We lack a true understanding of context and there’s been little if any connection of the dots between the science and its application.

Why the divide?

Clearly there’s a divide, but why? To start, most academics in university don’t know context. The teachers are not to blame, but they simply don’t know. Why would they? They’ve never had the experience. Martin and I began there too, and didn’t understand context ourselves until we got our chance to enter the high performance world. This experience bestowed hard lessons, but today allows us the ability to step back and forth across the void as needed, perhaps enabling us the ability to provide something a bit more digestible for everyone; academics and practitioners alike.

But to finish this point, we are today left with two issues on both sides of the divide that keep the worlds separate; we believe that both need addressing: