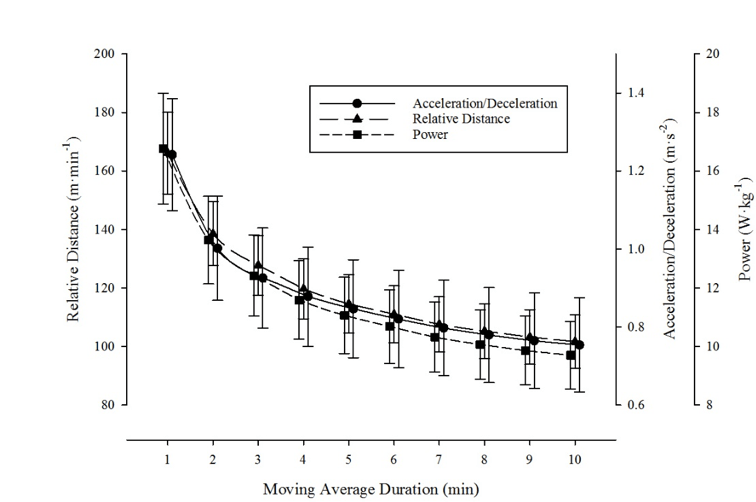

Figure 1. Maximum running intensities of rugby league match-play across a range of rolling average durations. Data are presented as mean ± SD for each outcome variable.1

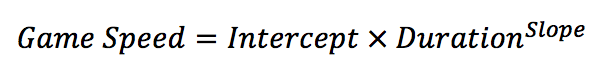

More detail about this technique can be found on a blog post I recently wrote, along with an associated spreadsheet for calculating game speed using your own data. Put simply, this method allows us to prescribe and monitor skill-based training drills and GBHIIT more accurately relative to the most intense period of competition. Likewise, this process permits us to prescribe our GBHIIT so as to simultaneously develop our physical capacities alongside the specific skill and game-based decision-making demands of team sport play. Such a technique is clearly preferable to traditional conditioning from the point of view of the coaching staff, as the technical and tactical abilities are being constantly overloaded. Therefore, the monitoring of training relative to game speed is a simple, effective and invisible way to drive intensity during training.

In some cases, we may find that players are unable to reach the required intensities of competition during training. In this case, such players may benefit from supplementary conditioning strategies (shuttle-based short interval HIIT, for example) to increase their physical capacities and to enable the intensity requirements of our skill-based training. It is important to note that these methodologies are not intended to replace traditional conditioning practices, but instead to serve as useful alternatives during the competitive phase when time constraints are at their highest.

Problem 2: Ok, so we are training at an appropriate intensity, but is it enough to sustain or further enhance our players’ fitness levels?

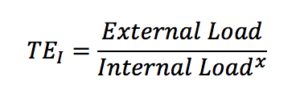

Solution 2: The Training Efficiency Index (TEI)

Now that we know we are training at the right intensity, the next thing we need to assess is how our athletes are responding to their training. This is the focus of Chapter 9 in the forthcoming book and course you will find on HIIT Science. Quantifying external training load (Chapter 8) is relatively straightforward. Just ask a player to wear a GPS and we can get a decent idea of what’s occurred from an external training load standpoint. Unfortunately, assessing the player’s internal (physiological) load is more complicated. There are a limited number of ways we can go about determining the internal load, each with their own varying level of logistical and financial limitations. Determining internal load using heart rate (HR) may be most useful, as the marker is relatively reliable and sensitive to fluctuations in intensity throughout a session. Nevertheless, the measure has a number of limitations including lag time in response to intensity, HR inertia, notwithstanding skin connectivity and player buy-in issues. Session rating of perceived exertion (RPE) is simple, free, and can serve as a useful global non-specific measure. However, this method depends on athletes responding accurately, which can be difficult to achieve with large groups of athletes in a short space of time.

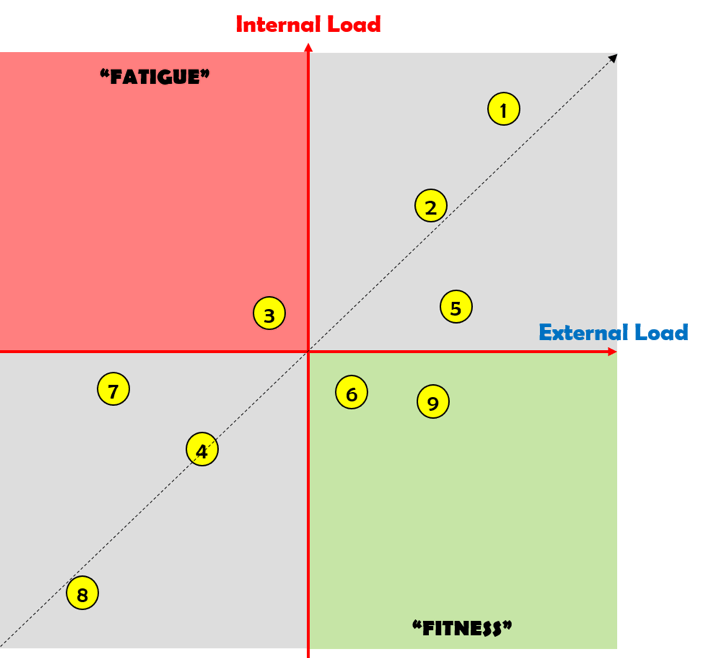

Specific to fitness tests themselves, submaximal running tests have become increasingly popular due to their short durations, low physiological burden, and relative ease of implementation.3 These standardized tests control the volume and intensity of the external work completed, meaning fluctuations in the internal response (HR) from week-to-week may be reflective of positive/negative training effects. However, we need to ask ourselves – is standardization of the external component of the test really necessary if we are constantly measuring it using GPS? Instead, by just assessing our internal load (i.e. HR response) in the context of the measured external load, we can attain a similar (and invisibly collected) snapshot assessment without needing to perform a fitness test at all (Figure 2).

More detail about this technique can be found on a blog post I recently wrote, along with an associated spreadsheet for calculating game speed using your own data. Put simply, this method allows us to prescribe and monitor skill-based training drills and GBHIIT more accurately relative to the most intense period of competition. Likewise, this process permits us to prescribe our GBHIIT so as to simultaneously develop our physical capacities alongside the specific skill and game-based decision-making demands of team sport play. Such a technique is clearly preferable to traditional conditioning from the point of view of the coaching staff, as the technical and tactical abilities are being constantly overloaded. Therefore, the monitoring of training relative to game speed is a simple, effective and invisible way to drive intensity during training.

In some cases, we may find that players are unable to reach the required intensities of competition during training. In this case, such players may benefit from supplementary conditioning strategies (shuttle-based short interval HIIT, for example) to increase their physical capacities and to enable the intensity requirements of our skill-based training. It is important to note that these methodologies are not intended to replace traditional conditioning practices, but instead to serve as useful alternatives during the competitive phase when time constraints are at their highest.

Problem 2: Ok, so we are training at an appropriate intensity, but is it enough to sustain or further enhance our players’ fitness levels?

Solution 2: The Training Efficiency Index (TEI)

Now that we know we are training at the right intensity, the next thing we need to assess is how our athletes are responding to their training. This is the focus of Chapter 9 in the forthcoming book and course you will find on HIIT Science. Quantifying external training load (Chapter 8) is relatively straightforward. Just ask a player to wear a GPS and we can get a decent idea of what’s occurred from an external training load standpoint. Unfortunately, assessing the player’s internal (physiological) load is more complicated. There are a limited number of ways we can go about determining the internal load, each with their own varying level of logistical and financial limitations. Determining internal load using heart rate (HR) may be most useful, as the marker is relatively reliable and sensitive to fluctuations in intensity throughout a session. Nevertheless, the measure has a number of limitations including lag time in response to intensity, HR inertia, notwithstanding skin connectivity and player buy-in issues. Session rating of perceived exertion (RPE) is simple, free, and can serve as a useful global non-specific measure. However, this method depends on athletes responding accurately, which can be difficult to achieve with large groups of athletes in a short space of time.

Specific to fitness tests themselves, submaximal running tests have become increasingly popular due to their short durations, low physiological burden, and relative ease of implementation.3 These standardized tests control the volume and intensity of the external work completed, meaning fluctuations in the internal response (HR) from week-to-week may be reflective of positive/negative training effects. However, we need to ask ourselves – is standardization of the external component of the test really necessary if we are constantly measuring it using GPS? Instead, by just assessing our internal load (i.e. HR response) in the context of the measured external load, we can attain a similar (and invisibly collected) snapshot assessment without needing to perform a fitness test at all (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A conceptual model for the integration of internal and external training loads as per the “invisible monitoring” framework.

Where x is a scaling factor, obtained as the slope of the relationship between the log-transformed internal and external load variables. A detailed description of how to calculate this metric can be found here, including a free spreadsheet for use.

Primarily, the benefit of the TEI is that no additional intervention is required (i.e. monitored invisibly), and just by assessing internal and external load simultaneously during any on-field training session (conditioning, skills training or matches), we can attain valuable information on the training status of our athletes. A recent study by Lacome et al.5 presents a comparable technique, where predicted HR responses to training drills are compared against actual HR results, similarly reducing the logistical burden of testing interventions. While an extra 10 minutes per week returned back to an elite program might not seem like a big difference, those in the trenches, including those you’ll read about in the sport application chapters of HIIT Science, will attest that this time-saving does have a positive impact on their playing groups.

Problem 3: Our players are looking flat, but their fitness levels are good. Where are we going wrong?

Solution 3: Within-session fatigue/readiness monitoring

In theory, we could have the fittest and most skillful team in the world, but if we run our players into the ground, it’s unlikely they’re going to perform at their best on game day. Therefore, it could be suggested that monitoring of fatigue and readiness on a regular basis can help ensure that players are operating at their optimal levels on game day. The possibilities for assessing fatigue and readiness are extensive, ranging from subjective wellness questionnaires, to biochemical profiling, or neuromuscular performance testing. However, as discussed in detail by Carling et al.6 recently, each of these interventions carries a significant burden, whether it be cost, implementation practicality, or simply lack of buy-in from coaches and players, not to mention the questionable importance of fatigue monitoring in the real-world setting. High-level players are more often than not able to perform irrespective of slight neuromuscular impairments, or elevated levels of acute muscle soreness. Unfortunately, good quality, practically-relevant research in such athletes is lacking due to the aforementioned perceived burden to athletes and coaches. This issue is difficult to circumvent, as sport science research cannot be the number one priority at this level. Therefore, we as practitioners must continue to strive for ways to extract relevant data using the information that we typically collect on a day-to-day basis – i.e. “invisibly”.

Specific to on-field performance, there are several possibilities for assessing fatigue/readiness during training and competition. For example, GPS-embedded accelerometers, coupled with customized data- processing software, enables practitioners to assess the neuromuscular and mechanical determinants of training and competition,7 which may have greater precision for detecting fatigue when compared to traditional time-motion analyses. Similarly, changes in the contribution of each vector (i.e. x, y or z) to the total PlayerLoadTM achieved during match play have been shown to be associated with countermovement jump variables amongst top-level Australian soccer players.8

Given the primarily horizontal nature of force output during many field-based sports such as soccer and the football codes, assessed horizontal force production capabilities may reveal further insights into the athletes’ readiness to perform. Practical field-based methods of assessing the mechanical profile of sprint acceleration have been developed,9 which allow the determination of horizontal force production during short but maximal sprint acceleration efforts. Although these data are useful for detecting fatigue,10 they can be difficult to implement practically due to the associated additional fatigue and injury risk, the need for players to sprint maximally, or simply the logistics of scheduling during the in-season period. Within-session estimates of the mechanical properties of sprinting would be ideal, though current tracking technologies seem to be unable to assess these metrics accurately.

Summary

The examples I have discussed in this post are just a few of many in the team sport context. The best sport science programs I have seen are highly-integrated, and complement the goals of the team and other members of the performance staff. Most importantly, the “invisible monitoring” concept outlined within this post ultimately allows us to reduce the testing burden placed on the athletes themselves. Since adopting this approach, I have been able to answer questions asked by both coaches and performance staff, without taking time away from the development of the playing group. These invisible techniques have developed over time, and will continue to do so, due to both technological advancements, and our collective sharing as practitioners of the enhanced understanding of their efficacy in high-level sport.

About the author: Jace Delaney is a sport scientist currently working as the Director of Performance and Sports Science with the University of Oregon’s athletic program. His website Sport Performance Explained is a platform where he and fellow colleague Matt Jones share their opinions concerning elite athletic performance, with the overarching focus on linking research to practice.

References

Where x is a scaling factor, obtained as the slope of the relationship between the log-transformed internal and external load variables. A detailed description of how to calculate this metric can be found here, including a free spreadsheet for use.

Primarily, the benefit of the TEI is that no additional intervention is required (i.e. monitored invisibly), and just by assessing internal and external load simultaneously during any on-field training session (conditioning, skills training or matches), we can attain valuable information on the training status of our athletes. A recent study by Lacome et al.5 presents a comparable technique, where predicted HR responses to training drills are compared against actual HR results, similarly reducing the logistical burden of testing interventions. While an extra 10 minutes per week returned back to an elite program might not seem like a big difference, those in the trenches, including those you’ll read about in the sport application chapters of HIIT Science, will attest that this time-saving does have a positive impact on their playing groups.

Problem 3: Our players are looking flat, but their fitness levels are good. Where are we going wrong?

Solution 3: Within-session fatigue/readiness monitoring

In theory, we could have the fittest and most skillful team in the world, but if we run our players into the ground, it’s unlikely they’re going to perform at their best on game day. Therefore, it could be suggested that monitoring of fatigue and readiness on a regular basis can help ensure that players are operating at their optimal levels on game day. The possibilities for assessing fatigue and readiness are extensive, ranging from subjective wellness questionnaires, to biochemical profiling, or neuromuscular performance testing. However, as discussed in detail by Carling et al.6 recently, each of these interventions carries a significant burden, whether it be cost, implementation practicality, or simply lack of buy-in from coaches and players, not to mention the questionable importance of fatigue monitoring in the real-world setting. High-level players are more often than not able to perform irrespective of slight neuromuscular impairments, or elevated levels of acute muscle soreness. Unfortunately, good quality, practically-relevant research in such athletes is lacking due to the aforementioned perceived burden to athletes and coaches. This issue is difficult to circumvent, as sport science research cannot be the number one priority at this level. Therefore, we as practitioners must continue to strive for ways to extract relevant data using the information that we typically collect on a day-to-day basis – i.e. “invisibly”.

Specific to on-field performance, there are several possibilities for assessing fatigue/readiness during training and competition. For example, GPS-embedded accelerometers, coupled with customized data- processing software, enables practitioners to assess the neuromuscular and mechanical determinants of training and competition,7 which may have greater precision for detecting fatigue when compared to traditional time-motion analyses. Similarly, changes in the contribution of each vector (i.e. x, y or z) to the total PlayerLoadTM achieved during match play have been shown to be associated with countermovement jump variables amongst top-level Australian soccer players.8

Given the primarily horizontal nature of force output during many field-based sports such as soccer and the football codes, assessed horizontal force production capabilities may reveal further insights into the athletes’ readiness to perform. Practical field-based methods of assessing the mechanical profile of sprint acceleration have been developed,9 which allow the determination of horizontal force production during short but maximal sprint acceleration efforts. Although these data are useful for detecting fatigue,10 they can be difficult to implement practically due to the associated additional fatigue and injury risk, the need for players to sprint maximally, or simply the logistics of scheduling during the in-season period. Within-session estimates of the mechanical properties of sprinting would be ideal, though current tracking technologies seem to be unable to assess these metrics accurately.

Summary

The examples I have discussed in this post are just a few of many in the team sport context. The best sport science programs I have seen are highly-integrated, and complement the goals of the team and other members of the performance staff. Most importantly, the “invisible monitoring” concept outlined within this post ultimately allows us to reduce the testing burden placed on the athletes themselves. Since adopting this approach, I have been able to answer questions asked by both coaches and performance staff, without taking time away from the development of the playing group. These invisible techniques have developed over time, and will continue to do so, due to both technological advancements, and our collective sharing as practitioners of the enhanced understanding of their efficacy in high-level sport.

About the author: Jace Delaney is a sport scientist currently working as the Director of Performance and Sports Science with the University of Oregon’s athletic program. His website Sport Performance Explained is a platform where he and fellow colleague Matt Jones share their opinions concerning elite athletic performance, with the overarching focus on linking research to practice.

References

- Delaney JA et al. Acceleration-based running intensities of professional rugby league match play. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016; 11, 802-809.

- Delaney JA et al. Modelling the decrement in running intensity within professional soccer players. Sci Med Football. 2017; 2(2), 86-92.

- Veugelers KR et al. Validity and reliability of a submaximal intermittent running test in elite Australian football players. J Strength Cond Res. 2016; 30(12), 3347-3353.

- Delaney JA et al. Quantifying the relationship between internal and external work in team sports: development of a novel training efficiency index. 2018; 2(2), 149-156.

- Lacome M et al. Monitoring players’ readiness using predicted heart rate responses to football drills. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018.

- Carling C et al. Monitoring of post-match fatigue in professional soccer: welcome to the real world. Sports Med. 2018.

- Buchheit M et al. 2018. Neuromuscular responses to conditioned soccer sessions assessed via GPS-embedded accelerometers: Insights into tactical periodization. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018; 13(5), 577-583.

- Rowell AE et al. A standardized small sided game can be used to monitor neuromuscular fatigue in professional A-League football players. Front Physiol. 2018.

- Samozino P et al. A simple method for measuring power, force, velocity properties, and mechanical effectiveness in sprint running. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016; 26(6), 648-658.

- Marrier B et al. Quantifying neuromuscular fatigue induced by an intense training session in rugby sevens. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2016; 12(2), 218-223.