Introduction

Sleep has long been considered a vital recovery behaviour needed for athletic success (1). However, athletes often sleep poorly due to the effects of early morning training (2), trans-meridian travel (3), mental battles with pre-competition thoughts and nervousness (4), and/or sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity following late-night competition (5).Despite this, relatively few studies have actually examined the effects of sleep on athletic recovery and performance.While there is some evidence that sleep extension (i.e. increasing habitual sleep duration) may improve sprint performance and shooting accuracy in basketballers (6), and serving accuracy in tennis players (7), the impact of sleep extension on the performance of endurance athletes had not been investigated. What’s more, although endurance athletes routinely train and compete on consecutive days (e.g., cyclists during tour races), little is known concerning the cumulative effects of sleep over consecutive nights on the performance of endurance athletes.

What did we do?

Nine trained endurance cyclists/triathletes (mean ± SD, 63 ± 6 mL·kg-1·min-1) undertook three conditions that each required endurance time-trials to be completed on four consecutive days (D1-D4). The time-trials required a set amount of work (kJ) to be performed as quickly as possible, whereby target work was individualised for each cyclist and estimated to take around 1 h to complete.Athletes slept normally prior to the first time-trial of each condition, but on the three subsequent nights, time in bed remained normal (normal sleep condition), was reduced by 30% (sleep restriction condition), or was extended by 30% (sleep extension condition).Time in bed interventions were based on participants’ habitual sleep that was monitored with actigraphy prior to commencing the study. Actigraphy was also used to monitor sleep immediately prior to, during, and post, each experimental condition. Finishing time and perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded for the time-trials. A minimum 7-day washout period separated experimental conditions.

What did we find?

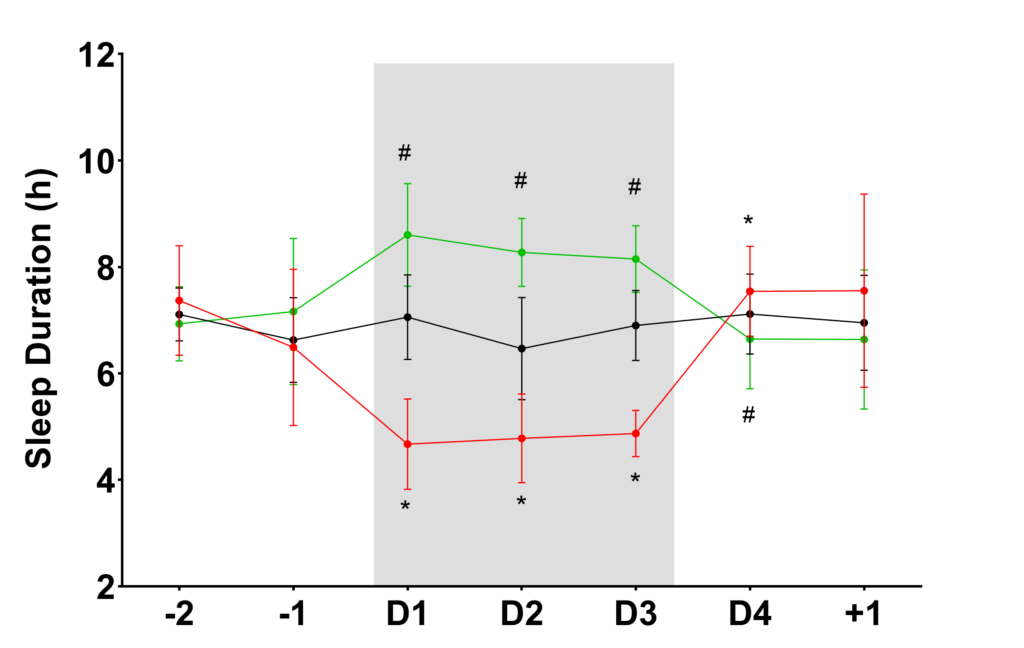

Sleep duration was similar for all conditions in the lead up to the first time-trial, with athletes typically sleeping around 14 h in the 48 h period prior to D1. On subsequent intervention nights (nights of D1, D2, and D3 – shaded area in Figure 1) athletes averaged just under 7 h sleep per night in the normal sleep condition, just under 5 h per night in the sleep restriction condition, and more than 8 h per night in the sleep extension condition (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sleep duration during the sleep restriction (red), normal sleep (black), and sleep extension (green) conditions. Time in bed interventions prescribed on nights of D1, D2, and D3 (grey shaded area). # Different (p < 0.025) to both normal sleep and sleep restriction conditions. * Different (p < 0.025) to normal sleep and sleep extension conditions. Data presented as mean ± SD. Source: Roberts et al. (8).

Figure 1. Sleep duration during the sleep restriction (red), normal sleep (black), and sleep extension (green) conditions. Time in bed interventions prescribed on nights of D1, D2, and D3 (grey shaded area). # Different (p < 0.025) to both normal sleep and sleep restriction conditions. * Different (p < 0.025) to normal sleep and sleep extension conditions. Data presented as mean ± SD. Source: Roberts et al. (8).

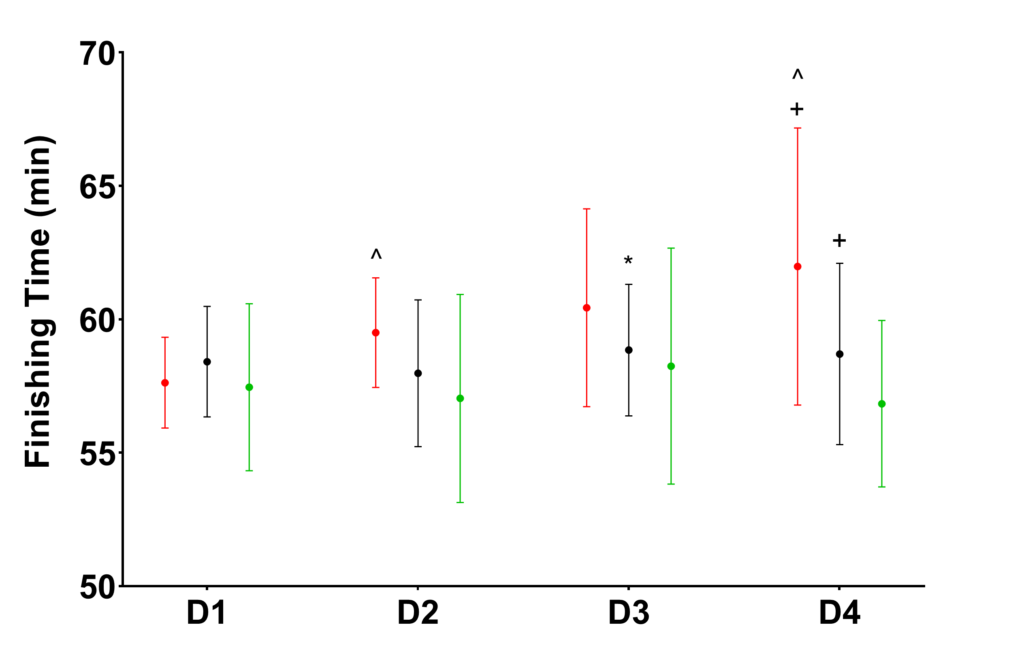

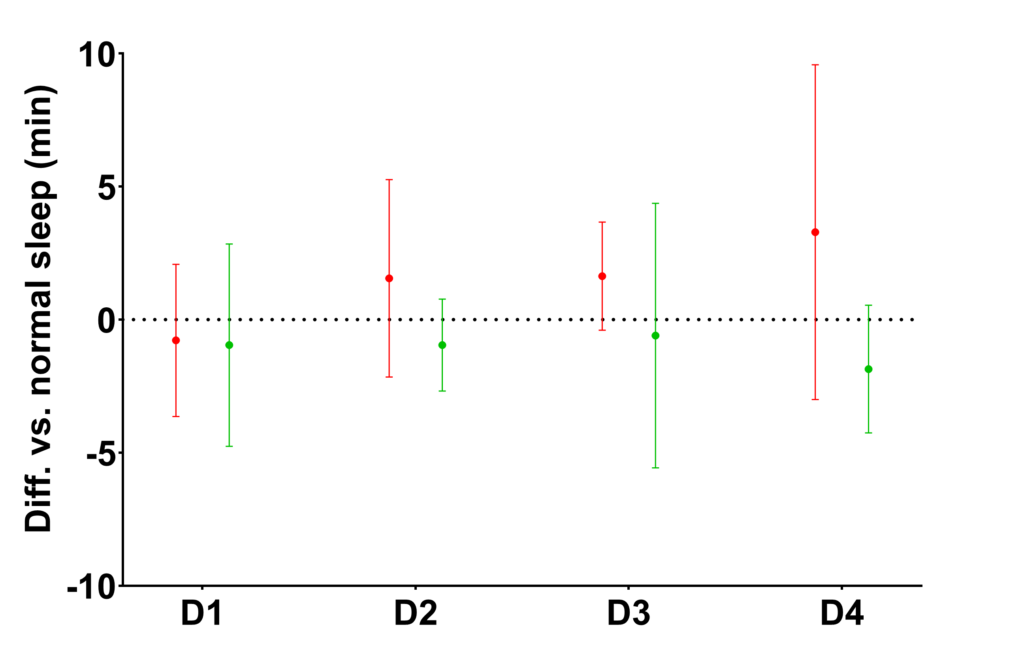

Finishing time was typically two minutes faster after three nights of sleep extension compared to after three nights of normal sleep (58.7 min vs 56.8 min) – a 3% improvement in performance (Figure 2).In contrast, performance was impaired by sleep restriction, as finishing time was slower after just two nights of sleep restriction compared to after two nights of normal sleep (60.4 min vs 58.8 min) – a 3% impairment in performance. In addition, while performance was consistent during both sleep extension and normal sleep conditions, this was not the case for the sleep restriction condition, as finishing times were slower on D2 and D4 compared with D1.

Figure 2. Time-trial finishing times across the four days of testing (D1-D4) for the sleep restriction (red), normal sleep (black), and sleep extension (green) conditions. + Different (p < 0.025) to the sleep extension condition. * Different (p < 0.025) to the sleep restriction condition. ^ Different (p < 0.05) to D1 of the same condition. Data presented as mean ± SD. Source: Roberts et al. (8).

Figure 2. Time-trial finishing times across the four days of testing (D1-D4) for the sleep restriction (red), normal sleep (black), and sleep extension (green) conditions. + Different (p < 0.025) to the sleep extension condition. * Different (p < 0.025) to the sleep restriction condition. ^ Different (p < 0.05) to D1 of the same condition. Data presented as mean ± SD. Source: Roberts et al. (8).

Figure 3. Difference in time-trial finishing times compared with the normal sleep condition across the four days of testing (D1-D4) for the sleep restriction (red) and sleep extension (green) conditions. Data presented as mean ± SD.

Interestingly, cyclists reported similar RPE scores during all time-trials regardless of how much sleep they obtained. So all time-trials felt just as hard despite differences in finishing time. Therefore, prior sleep duration seems to affect performance by altering the perceived effort of a given exercise intensity (i.e., power output) such that sleep extension allows higher exercise intensities to be tolerated.What should endurance athletes know?

Take it to the bank. A little extra sleep per night, when accumulated over several nights, can improve endurance performance.This study indicates sleep is particularly important for endurance athletes competing across consecutive days (e.g., cyclists during tour races).However, other athletes competing over consecutive days, or undertaking congested competition schedules, may also benefit from sleep extension. There are also implications for training outcomes, as extra sleep during training periods will likely improve training tolerance. Athletes should accordingly prioritise sleep during both training and competition periods. Aim for small, consistent improvements. An extra half-an-hour per night for a couple of weeks adds up to an additional 7 h of sleep – that’s an extra night of sleep in the bank!

What can sport scientists / coaches do?

- Give your athletes time to sleep. Early morning training sessions and late-night competition reduce the time available for sleep (5, 9). So if possible, avoid early morning training — try to start training > 7am. If your athletes compete at night, make sure you give them time over the next few days to catch up on sleep. And remember, daytime napping is a good way to supplement night-time sleep (10).

- Provide sleep hygiene education. Sleep hygiene refers to the adoption of behaviours that promote sleep (e.g., cool bedroom, low-light environment before bed, consistent sleep-wake schedule etc.) and the avoidance of behaviours that disrupt sleep (e.g., evening screen time, caffeine intake etc.). Sleep hygiene education has been shown to improve the sleep of athletes (11).

- Don’t stress about it. This may make sleep more elusive. Everyone occasionally has a bad night – so tell your athletes not to worry about it. It’s normal. Focus more on weekly or monthly sleep patterns rather than individual nights.

This study is published as ‘Extended Sleep Maintains Endurance Performance Better than Normal or Restricted Sleep’ in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise (8).

This study is published as ‘Extended Sleep Maintains Endurance Performance Better than Normal or Restricted Sleep’ in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise (8).

About the author

Spencer Roberts, PhD, is a sport scientist from Melbourne, Australia. His research has focused on characterising the sleep of athletes and understanding its effects on performance and health. He has consulted with elite and professional sporting organisations on strategies for improving and monitoring athlete sleep. Follow him on Twitter @SSHRoberts.

Spencer Roberts, PhD, is a sport scientist from Melbourne, Australia. His research has focused on characterising the sleep of athletes and understanding its effects on performance and health. He has consulted with elite and professional sporting organisations on strategies for improving and monitoring athlete sleep. Follow him on Twitter @SSHRoberts.

References

- Venter RE. Perceptions of team athletes on the importance of recovery modalities. Eur J Sport Sci 14(supp1):S69-S76, 2014.

- Sargent C, Halson S, Roach GD. Sleep or swim? Early-morning training severely restricts the amount of sleep obtained by elite swimmers. Eur J Sport Sci. 14(supp1):S310-S315, 2014.

- Fowler PM, McCall A, Jones M, Duffield R. Effects of long-haul transmeridian travel on player preparedness: Case study of a national team at the 2014 FIFA World Cup. J Sci Med Sport 20(4):322-327, 2017.

- Juliff LE, Halson SL, Peiffer JJ. Understanding sleep disturbance in athletes prior to important competitions. J Sci Med Sport 18(1):13-18, 2015.

- Sargent C, Roach GD. Sleep duration is reduced in elite athletes following night-time competition. Chronobiol Int 33(6):667-670, 2016

- Mah CD, Mah KE, Kezirian EJ, Dement WC. The effects of sleep extension on the athletic performance of collegiate basketball players. Sleep 34(7):943, 2011

- Schwartz J, Simon RD. Sleep extension improves serving accuracy: A study with college varsity tennis players. Physiol Behavior 151:541-544, 2015.

- Roberts SSH, Tep WP, Aisbett B Warmington SA. Extended sleep maintains endurance performance better than normal or restricted sleep. Med Sci Sport Exerc 51(12):2516-2523, 2019.

- Sargent C, Lastella M, Halson SL, Roach GD. The impact of training schedules on the sleep and fatigue of elite athletes. Chronobiol Int 31(10):1160-1168, 2014

- Romyn G, Lastella M, Miller DJ, Versey NG, Roach GD, Sargent C. Daytime naps can be used to supplement night-time sleep in athletes. Chronobiol Int 35(6):865-868, 2018.

- Driller MW, Lastella M, Sharp AP. Individualized sleep education improves subjective and objective sleep indices in elite cricket athletes: A pilot study. J Sports Sci 37(17):2021-2025, 2019.