Demands of The Sport

Unlike indoor volleyball, beach volleyball is played with two people and on the sand. There is no coaching allowed during matches or substitutions. This means that athletes must have the technical, tactical and physical tools needed to solve problems for themselves in order to succeed. There is nowhere to hide! Matches are a best of 3 set format; the first two sets are to 21 points and the third set (if required) to 15 points. Matches are typically 40-45 minutes in duration (1), with the majority of rallies being short, typically averaging 7 seconds, with 19-23 seconds rest (2). Athletes require the ability to repeat these short high-intensity efforts, with the first structural rest (30 seconds) coming after 21 points in the form of a technical timeout. Points at the elite level tend to be derived from explosive actions that include jumping, diving, short sprints and changes of direction.Players may have to jump upwards of 120 times in a match, make 60 attacks (approach & spike) and dive and get up from the ground up to 10 times (2, 3).This highlights the repeated power nature of the sport. The tour, organized by the FIVB, operates in a tiered system, with 1- to 5-star ranked events. The Continental Championships, World Championships and Olympics are the pinnacle events. Athletes with Olympic aspirations are typically competing in 4- and 5-star events and the major championships. Tournament formats vary, but 4- and 5-star events are generally played over 5 days, with up to 3 matches in a day and as little as one hour between matches.

Players will commonly compete in over 15 events per year with consecutive tournaments requiring routine intercontinental travel.On top of this, events are played in the extremes of various environmental conditions, such wind, high temperatures and rain.

Physicality Influences Team Technical & Tactical Strategies

Style of play in the sport also adds an additional layer of context. With only two athletes on the court, the aim is to hit the ball past one blocker and defender. There are two broad styles of attack that are used to achieve this as follows: 1) ‘shooting’, which involves using vision to identify the open space and playing a loopy shot over the blocker, and 2) ‘hard driven’, which involves delivering the ball with power to the opposite side of the net. We have the philosophy of giving the athlete as many attacking options as possible. Power volleyball has become a successful trademark for certain teams on the beach volleyball tour. This style involves using a high percentage of hard driven offences and minimal shooting plays. This style of play needs to be supported by well-developed physical qualities, specifically the ability to repeat high-intensity efforts. Feeding further into the strategy of the game, we have what I call the negative or positive spiral. The simplest tactical choice in beach volleyball is deciding which player you will target on the serve. This determines who is most likely to attack the ball. Imagine you’ve been served and have made an error on attack. You can be certain that the next ball is coming to you. You have 12-20 seconds to get back into position, dust the sand off and try again!Fatigue resistance in this scenario is critical in the outcome of subsequent points.If you can recover effectively, you can have a better chance of having a slightly clearer head, making a better tactical decision, and producing an explosive action that can be well executed technically. And if not, guess what? You’re that little bit less recovered and the next ball is on you again. You’ve got to find a solution. In this sort of scenario, the confidence boost of a well-developed aerobic system to assist in recovery between points is huge. Knowing that they can serve you all day and that you can keep exploding and powering the ball with all of your offensive options available is a significant advantage.

Physical Contribution to Performance

Whilst having significant physical attributes as a player is vital, it remains a sport of technical execution, tactical awareness and decision making. In order to support the development of these qualities, coaches will generally want players on the court as much as possible. The high repetition of these skills puts a significant strain and demand on the musculoskeletal system, with the most common injuries in beach volleyball athletes being patella tendinopathies, overuse injuries of the shoulder and lower back complaints (4, 5). A significant proportion of the physical program therefore is dedicated to improving the resilience of tissues in order to handle these high demands. Also, there is a large importance placed on the strength and power development needed to support these high-intensity efforts. There’s not much point being able to repeat efforts all day if the output (jump height, spike velocity) aren’t at the required levels. Therefore, we first emphasize being able to produce high-intensity efforts before focusing on the ability to repeat them. As a result, the following goals seem logical in terms of physical preparation for beach volleyball players: – Optimising availability to train and compete, in order to allow development of technical and tactical competencies – Developing strength and power to support the explosive actions seen on court (move fast, jump high, hit hard) – Developing high levels of tissue tolerance to be better placed to absorb the repetitive stresses on the musculoskeletal system – Developing the ability to repeat (and recovery from) high-intensity efforts (point after point, match after match, day after day) – Enduring the stresses of travel, time zone adjustment and playing in environmental extremesHigh-Intensity Interval Training

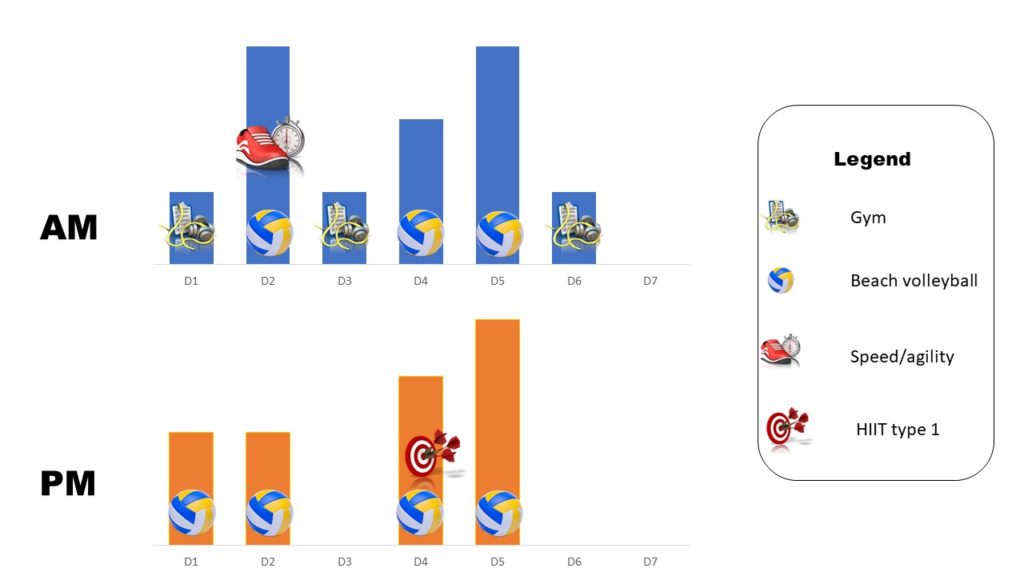

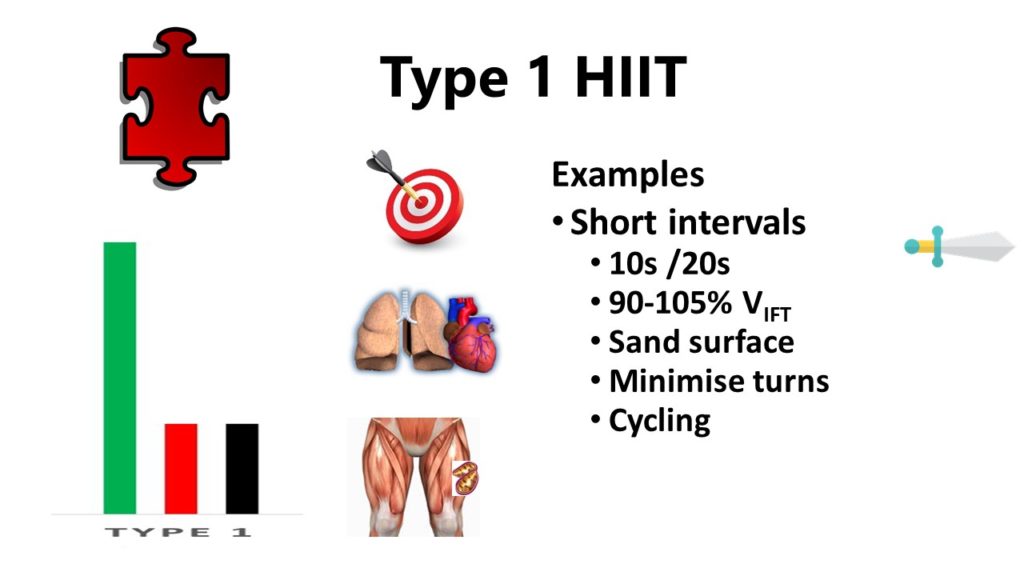

Beach volleyball requires development of all key physiological systems to varying degrees – aerobic, anaerobic and neuromuscular targets (Targets 1-6). We aim to hit all targets at various stages in the training year. Speed and strength sessions are used year-round to target the neuromuscular system (Type 6).The nature of sport-specific beach volleyball training naturally supports the targeting of the aerobic, anaerobic and neuromuscular pathways (Type 2, 3, 4).Repeated sprint training is occasionally used to achieve a large anaerobic and neuromuscular stimulus (Type 5). But the area I’d like to highlight is the use of short intervals to target development of the aerobic system, whilst minimising the anaerobic and neuromuscular responses (Type 1). While the explosive nature of beach volleyball suggests intuitively that the sport is all about the anaerobic and neuromuscular system, the aerobic system is also important to support recovery from the repeated high-intensity efforts on the court (6), and for building the overall work capacity to absorb the previously mentioned stressors (travel, environmental, etc). With the various competing demands in the training schedule (Figure 1), we need the maximal return on investment from our HIIT sessions. They need to be time efficient and simple to conduct. Additionally, minimising the neuromuscular load so as not to influence key volleyball and strength sessions in the following days is a consideration.

Figure 1: Example weekly training schedule during the specific preparation phase

Figure 1: Example weekly training schedule during the specific preparation phase

Figure 2: Type 1 HIIT

Figure 2: Type 1 HIIT

To prescribe intensity, we implemented the 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test on the sand.

This allows us to find a terminal speed (VIFT) and we can split the squad into a few groups with a specific target distance for each group based on VIFT (7). The distance can be adjusted by +/- 2 meters to achieve the right intensity dependant on the player and sand surface. Another constraint with court-based sports is the space available to run. Fortunately, we train in a facility with three courts next to each other, allowing a 36-metre distance across the back of the courts. Running 10 second efforts at 90-105% VIFT typically results in target distances of 40-55m, which allows us to achieve the prescribed distance in the 10 second work interval with only a single turn, limiting neuromuscular strain. This allows us to complete our 2-3 x 8-10 min of 10 s @ 90-105% VIFT with 20 s passive recovery between repetitions easily in our facility. This session is also easily implemented in travel scenarios as athletes will most often be able to access some sand. We have experimented with conducting some sessions on grass, allowing longer straight line running distances and a softer surface, but our experience is that athletes are highly adapted to the sand surface and this variation can flare up musculoskeletal complaints, typically in the Achilles and calves. If given a longer training block and with a long-term view of broadening an athlete’s movement bandwidth, there might be some merit in doing some longer straight line running on grass. Completing similar sessions on a stationary bike is another way we may limit the neuromuscular load. Until now, the implementation of this short interval session has proven to be effective with both coaching staff and athletes due jointly to the short time investment and the accountability of the known target distance. We have observed improvements on repeated sprint testing and anecdotal reports of a positive transfer to match play performance. A future step is to better quantify this transfer to the court by looking closer at jump height decrement and similar metrics. In summary, I hope I’ve been able to offer practitioners considering to work in the sport a snapshot view of the contextual factors that we deal with in the beach volleyball world, alongside useful examples of how HIIT training can be shaped to help us solve the programming puzzle. Optimal conditioning for the sport will remain a dynamic challenge led by context, but the framework provided by HIIT Science gives us a solid foundation to build content we can use to begin to solve the puzzle.🏐🏝🏖 🇧🇷 👏🏻

— 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test (@30_15IFT) May 3, 2020

30_15IFT adapted to #beachvolley @cangacovoleidepraia@brunotorresjp@fabio_sportsci @riceler_waske

@ernestovogado @mart1buch @hiitscience pic.twitter.com/iUIP8dABTu

About the author

David Jones is a Strength & Conditioning Coach with the Netherlands Olympic Committee and is currently working with the National Beach Volleyball Program. He has worked with beach volleyball and sailing in his time in The Netherlands and has previously worked for Tennis Australia as a Physical Performance Coach / Physiotherapist.

David Jones is a Strength & Conditioning Coach with the Netherlands Olympic Committee and is currently working with the National Beach Volleyball Program. He has worked with beach volleyball and sailing in his time in The Netherlands and has previously worked for Tennis Australia as a Physical Performance Coach / Physiotherapist.

Follow him on Twitter: @djones_151

References

- Palao JM, Valadés D, Manzanares P, Ortega E. Physical actions and work-rest time in men’s beach volleyball. Motriz Rev Educ Fis. 20(3):257-261. 2014.

- Natali S, Ferioli D, LA Torre A, Bonato M. Physical and technical demands of elite beach volleyball according to playing position and gender. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 59(1):6-9. 2019

- te Lintel Hekkert, N. Differences in actions between elite male blockers, defenders and universals during beach volleyball matches. Unpublished Data. 2018

- Jimenez-Olmedo JM, Penichet-Tomas A. Injuries and pathologies in beach volleyball players: A systematic review. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. 10(4):936-948. 2015.

- Jones, D. Injury Data of a National Beach Volleyball Squad. Unpublished Data. 2020

- Tomlin, D.L., Wenger, H.A. The Relationship Between Aerobic Fitness and Recovery from High Intensity Intermittent Exercise. Sports Medicine. 31:1–11. 2001.

- Buchheit M. The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test: 10 year review. Martin-BuchheitNet. 1:1-9. 2010. http://martin-buchheit.net/Dossiers/Buchheit-30-15IFT-10_yrs_review_(2000-2010).pdf.