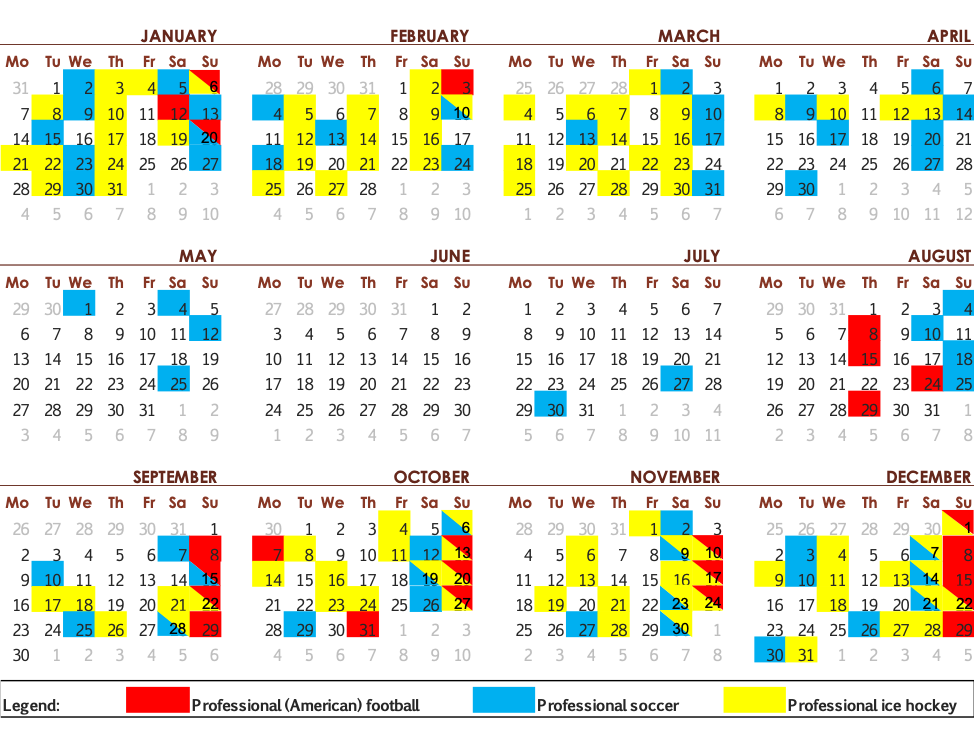

“For me context is key – from that comes the understanding of everything.” – Kenneth NolandIt comes as no surprise that Martin chose to open the HIIT Science blog series with this excellent post about context. It is a must-read article, which uses both the Ebbinghaus Illusion and the Dunning-Kruger Effect to illustrate his points, both of which are important considerations in sports science. As practitioners, we must be able to zoom into the minutia of what we are planning to do, such as the specifics of how we design a HIIT session. Additionally, however, we must also be able to zoom out in order to understand the wider context. This incredible video of the “Cosmic Eye” (shared with me by my colleague Will Greenberg) is a very cool reminder of perspective. In the context of sports, our “uniform universe” may well be the annual (or multi-annual) scheduling of sport. Figure 1 displays an example season for a Premier League football team (blue), a regular season NHL team (yellow), and a Superbowl-bound NFL team (red) [please note; where two games fall on the same day, the day is split into two colours]. Instantly, we can note that the context of a specific training session on any given day is very different when considered in the confines of each competition schedule. In addition, the relative end date of the season can vary for the sport depending on post-season success or lack thereof. So the context of the previous season needs to be taken into consideration when planning for the current season.

Figure 1. Schedule comparison across three professional sports.

“Competency is not in the knowledge and the skills per se, but in how we use our knowledge in accordance with the context”.Collaboration cannot succeed in an environment without a thorough understanding of its context. Curiosity

“There is power in understanding the journey of others to help create your own.” – Kobe BryantCuriosity drives innovation. It is described in this interesting article as “the fuel that powers science”. Within the article, a recent study is described that suggests curiosity is driven by the same neurobiological process as that of hunger (7). Thus it may not just be a figurative hunger for knowledge that drives our curiosity! In an eloquent, real-life example of the importance of curiosity in sport, Jeremy Sheppard wrote about the power of curiosity for practitioners studying performance in any new sport. Moreover, I believe that curiosity is an equally powerful tool for building relationships with colleagues. Walking into any new environment demands the ability to build relationships, and even more so when relationships are needed across different backgrounds. People in such situations can be very quick to share their own background, perhaps as a justification of their right to be there. However, first showing interest and curiosity in other people’s backgrounds may be the key trait you require if your aim is building the trust from others you require to effectively do your work. As the saying goes:

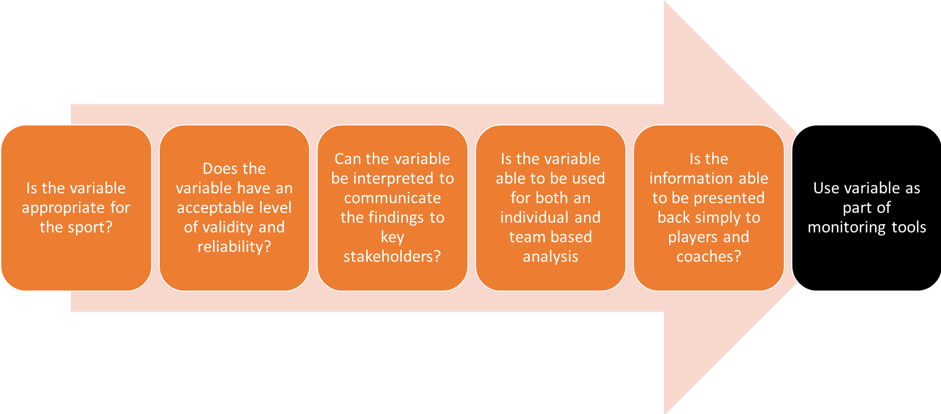

“we have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak”.Often in a team sports setting, you can learn the most in the places you might least expect, such as in the cafeteria or the kit/equipment room. One of the Equipment Managers I have worked with had been with the team since it had formed and thus worked with every player that had ever worn the jersey. Showing curiosity in his stories taught me a lot about the history and culture of the sport and the team, in much more detail than I could have gained from Wikipedia! The benefit of curiosity doesn’t just apply to the backgrounds of those around you, but also their thoughts and experiences in relation to performance aspects too. Finding out what has gone before, either in this specific environment or in other settings, can help to fast-forward collaboration towards the best approach to implementation. In his post, Steve Barrett talks about his progress chart for assessing whether a new technology should be brought into an environment. By showing curiosity with your colleagues as well as external peers, you can learn lessons from others in response to the questions on this continuum.

Figure 2. Steve Barrent’s progress chart to help decide if a variable is relevant/ useful within a sporting environment.

“Communication leads to community, that is, to understanding, intimacy and mutual valuing.” – Rollo MayI’m sure this section comes as no surprise to the reader. Every job description and advert lists good communication skills as a prerequisite. Teams simply cannot function without good communication. In the phenomenal book Culture Code (4), Daniel Coyle identifies three key skills that build a cohesive culture; build safety, share vulnerability, and establish purpose. Each of these three processes is underpinned by communication. Coyle lists “ideas for action” within each section and these include behaviours such as:

- overdo thank you’s

- make sure everyone has a voice

- over-communicate expectations

- be ten times as clear about your priorities as you think you should be

“This is why, when you bring data to a TV show, you run the risk of appearing supercilious and judgemental. Even – especially – if you’re actually right. People want to feel wanted and loved. That there is someone who will listen to them. To feel part of a family.”Now replace “TV show” in that quote with “coach” … Paradoxically, we know there is an interest from coaches in applying sport science knowledge in practice, for example, as demonstrated by this recent study in Kinesiology (2). So it appears to be how we are communicating this data that has the potential to receive backlash. Even twenty years ago, Dr Bill Sands wrote that scientists need to understand the problems that coaches face, but also need to improve the way they convey their research findings and to communicate these findings in “a language that can be easily understood by coaches” (10). The advancement of data science skills, including data visualisation, within sports science is helping us to bring data alive for those around us. For example, Mathieu Lacome, Ben Simpson and Martin Buchheit have published a fantastic two-part series on monitoring training status with player-tracking technology, available open-access via the Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal, and expanded even further in the HIIT Science book and course (5, 6). However, we also need to ensure we have built relationships with those around us in order to have the opportunity to communicate this data. I have previously written about the need to try to connect with coaches via their gut instincts and coaching eye, rather than with facts and figures, in a post that was inspired by Simon Sinek’s book “Start with Why”. Forming relationships and rapport with key stakeholders will help us to unearth the right questions, which may provide us with the opportunity to collaborate and ultimately find a missing 1% (or 0.1%!) that matters. Final Thoughts Implementing high-intensity interval training requires collaboration between key stakeholders. Fostering collaboration involves understanding the context of the sport, athlete, and situation, building relationships through curiosity in others, and effective communication. If an organization is open-minded enough to bring in staff from a variety of backgrounds, the benefit (and fun) can be in connecting the knowledge and experiences of those individuals, in order to collaborate in ways that moves performance of the athletes forward.

“All knowledge is connected to all other knowledge. The fun is in making the connections.” ― Arthur C. Aufderheide

About the author: Jo Clubb is currently the Applied Sports Scientist for the Buffalo Bills in the NFL. She has also worked for the Buffalo Sabres in the NHL, as well as Chelsea and Brighton and Hove Albion in English football (soccer). Along with her undergraduate degree from Loughborough University, Jo has earned a Masters degree in High Performance Sport from the Australian Catholic University. She also writes for the blog Sports Discovery.

About the author: Jo Clubb is currently the Applied Sports Scientist for the Buffalo Bills in the NFL. She has also worked for the Buffalo Sabres in the NHL, as well as Chelsea and Brighton and Hove Albion in English football (soccer). Along with her undergraduate degree from Loughborough University, Jo has earned a Masters degree in High Performance Sport from the Australian Catholic University. She also writes for the blog Sports Discovery.- Bangsbo J. The physiology of football – with special reference to intense intermittent exercise. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 619: 1-155, 1994.

- Brink MS, Kuyvenhoven JP, Toering T, Jordet G, and Frencken WGP. What do football coaches want from sport science? Kinesiology 50: 150-154, 2018.

- Carey DG, Drake MM, Pliego GJ, and Raymond RL. Do hockey players need aerobic fitness? Relation between VO2max and fatigue during high-intensity intermittent ice skating. J Strength Cond Res 21: 963-966, 2007.

- Coyle, Daniel. The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups. First edition. New York: Bantam Books, 2018.

- Lacome M, Simpson BM, and Buchheit M. Part 1: Monitoring training status with player-tracking technology. Still on the way to Rome. Aspetar 7: 54-63, 2018.

- Lacome M, Simpson BM, and Buchheit M. Part 2: Monitoring training status with player-tracking technology. Still on the way to Rome. Aspetar 7: 64-66, 2018.

- Lau JKL, Ozono H, Kuratomi K, Komiya A, and Murayama K. Hunger for knowledge: how the irresistible lure of curiosity is generated in the brain. bioRxiv 473975; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473975

- Mohr M, Krustrup K, and Bangsbo J. Match performance of high-standard soccer players with special reference to development of fatigue. J Sports Sci 21: 439-449, 2003.

- Montgomery DL. Physiology of ice hockey. Sports Med 5: 99-126, 1998.

- Sands WA. How can coaches use sport science? Mod Athl Coach 36: 8-12, 1998.

- Wellman AD, Coad SC, Goulet GC, and McLellan CP. Quantification of competitive game demands of NCAA division I college football players using global positioning systems. J Strength Cond Res 30: 11-19, 2016.